The following reflection is one of six focusing on the importance of university research initially posted a decade ago. The following, modified modestly here, appeared on January 8, 2012.

Sixth in a Series on Research

Escalating financial exigency increasingly encourages universities to turn to funded research as a stable source of capital. The pragmatic implications of this view are inarguable. However, the long-term outlook of research productivity is best vested in the value added to the learning experience. Cash flow is the result, not the cause.

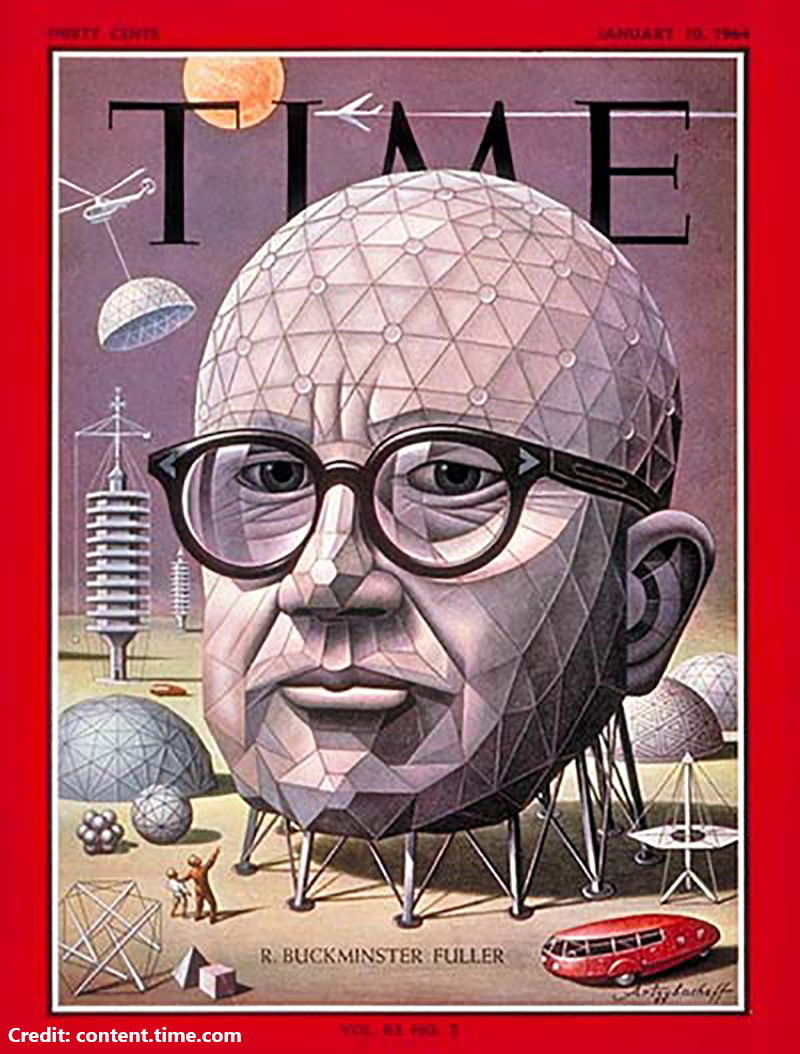

The Times cover of January 10, 1964, depicts an image of R. Buckminster Fuller formed from dodecahedrons or another hyperventilated crystallization of geometric space. At that time, the Southern Illinois University Carbondale professor and Nobel Prize nominee studied, with little outside support, complex relationships of math, science, technology and life. This eventually became known as Synergetics or “systems thinking.”

Fuller was driven by a desire to learn, not a desire to earn. These two aspirations are not mutually exclusive but co-dependent in the long haul. When the desire to learn reaches its apex, dollars are not far behind—vision is the glue that holds the two together. Ralph Waldo Emerson purportedly characterized it this way, “Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door.” Ideas create progress through value.

Fuller was gifted in making students think about what they were doing, why they were doing it and the social benefit of applied ideas. He was, by anybody’s definition, a scholar but secured sparse support for his striving. The coin of Fuller’s realm was intellectual acuity and concepts. So potent were his reflective excursions. He could hold student attention for six hours—they stretched the boundaries of their imaginations for a lifetime. And people got their money’s worth.

Philosopher and political theorist Michael Oakeshott suggested, “There is an important difference between learning which is concerned with the degree of understanding necessary to practice a skill, and learning which is expressly focused upon an enterprise of understanding and explaining.” Right he was. Right he is.

Fuller did not produce practical postulations that provided cash flow but rather a potently charged desire to know. A culture of scholarship is hard to predicate and, for some, may be considered an accountant’s can of worms. Too bad, but that’s the way it is and why vision is essential because, for a university, Fuller-like contributions are priceless in creating a campus’ intellectual climate.

Value is squeezed from faculty and students’ minds the way the juice is squeezed out of the pith of an orange…one drop at a time. The bottom-line model of a university is powered by headcount and capitation, student enrollment, graduation and retention rates. Every one of those business principles are important, but none necessarily leads to a better study environment for students. Likewise, a church inattentive to the pragmatics of management will go by the wayside, no matter how profound the theology is.

Powerful ideas are frequently gestated in pressure cookers of scholarship and creativity where people write, perform, paint, conceive and calculate with little funding. Yet, the ideas produced are what sustains the breath of university life. Ideas create institutional “theology.”

Beverly Sills knew it when she said, “Art is the signature of civilization.” True, it is. She could easily have added science too. When propelled adequately by power and purpose, high-energy particle physics likewise affects and is affected by the milieu in which it is conceptualized.

The public—those people who, for their children or themselves, decide to study at a university—can be fooled but only for a season. Eventually, universities without a meaningful intellectual environment will cease to attract good students when degrees are sold like snake oil and peddled like popcorn under the Big Top by Madison Avenue mongers.

People are too smart.

Our universities’ value rests in the intellectual and moral environment created and sustained by ideas. Contributions to that mélange come from disciplines of the written word, performing and plastic arts, the study of antiquities, mathematics, languages, religion, cultures, societies and some science for which little or no research funding is available, but value to society follows. And then the money flows.

The laws of the arithmetic of learning are at work. Hurston, Emerson, Oakeshott and Sills understood the concept.

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.