Fifth in a series on university struggles

Forward focus is essential. Over the past four decades, many faculty and university leaders have begun to believe that research and scholarly activity are more important than teaching. Graduate assistants, adjunct, and non-tenure-track faculty may be excellent teachers, but they have a tenuous relationship to the institution by definition, and are paid like janitors, and in the best instances, plumbers. Tolerating this equates teaching to caring for dirty floors or fixing leaking pipes. This is not a diminishment of the janitor or plumbers who know their craft. Instead, it’s a failing of leaders and faculty who don’t. And universities struggle.

For example, weak-kneed science abounds at too many universities, even purportedly good ones. The pressure to publish and its seemingly invincible measurability drives faculty to publish junk. Academic Conferences with peer-reviewed (other scientists affirm the works value) proceedings, web based journals with battalions of “peer” reviewers, and willing faculty in the chase for tenure, put out junk. I wish there was a better word for it. It is so pervasive that university leadership won’t call it what it is for fear of upsetting the apple cart, or, equally disturbing, throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Something is broken, and the basis of science, the idea of being able to replicate the finding of an experiment as reported, is in question. John Ioannidis, a medical professor at Stanford University, makes the point adamantly, “…false findings may be the majority or even the vast majority of published research claims.” Way too much of what is published is junk.

As a faculty member and university leader, I have participated in the perpetuation of weak scholarship for its superficial clarity in professorial evaluation at the expense of measuring good teaching because it is purportedly, too difficult to measure. Yet, we all know excellent teaching when we see it, and worse yet, we hold our noses and turn our heads winking-and-nodding as miserable teaching is passed off as something other than what it is: junk. The system is difficult to buck. The crime is simply understood: it is easier to assuage tenure protected poor teachers with the myth that even poor scholarship has more value when published than the negative impact of poor teaching. Absolutely wrong. The best research universities are frequently recognized for excellence in teaching. Quality follows quality and effective universities demand it in every aspect of work.

The peer review process is blind. The scholar’s work is reviewed by unknown (blind) reviewers ostensibly weeding out bias, professional jealousy, favoritism, and cronyism. These same principles should be applied to teaching. When students subjected to weak-kneed teaching are willing to say so through teaching feedback instruments, and do so semester after semester, their concerns should be attended to with forcefulness akin to the gospel-like accolades of blind peer review. Instead, universities are often dismissive of consistently poor teaching evaluations, with the admonition that “students” are not fit to judge. The result is predictable: Junk science is heralded as valuable scholarly activity. Junk teaching is ignored: Students don’t know what they’re talking about.

A faculty member once came to see me regarding her teaching evaluations. She was ecstatic about her “marks,” and felt that this response from students was ironclad evidence of teaching excellence. The next semester she posted a significantly lower assessment of teaching prowess from her students. Her response? Students “were just students” and could not be counted upon to rightly judge her ability to teach. I said, “Jane (not her real name), how can the students go from experts to morons in less than 12 months? You can’t have it both ways.” Upon reflection she concurred that her view of the students’ ability to “grade” her teaching was biased by the kind of grade she “earned.”

Additionally, the focus on the value of scholarship is its impact on student learning — teaching first — and nothing else. Every proposal for a sabbatical, or request for university support for research, should require a Pedagogical Impact Report estimating the influence of the intellectual work on teaching?

Such interdependency is the mark of a great university. Too many universities, worry about too much that has too little to do with excellent teaching.

Predictably, they struggle.

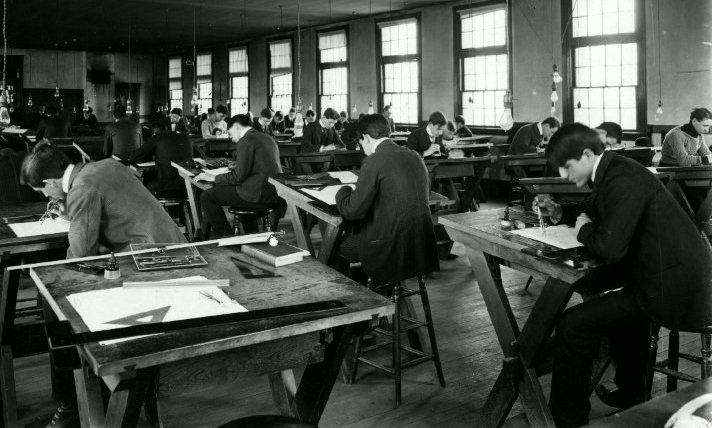

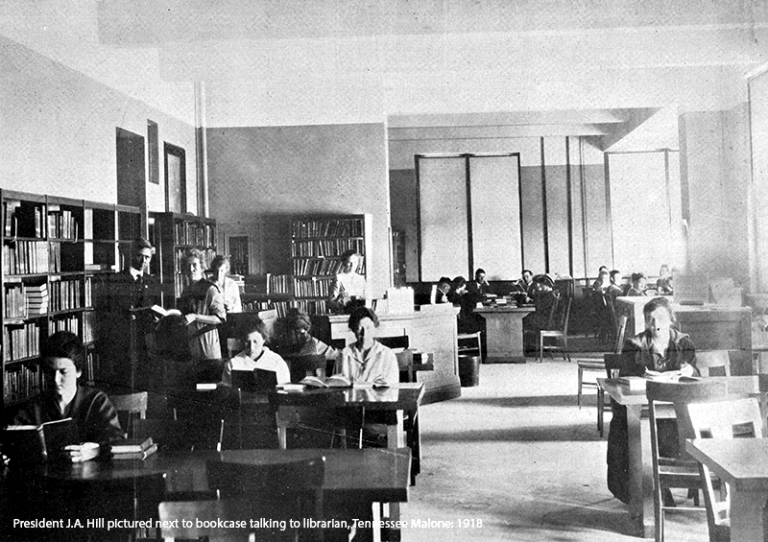

Photo Credit: https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/handle/1811/37435.

[…] http://walterwendler.com/2015/11/teaching-first/ […]

One of the most important pieces you have written. And so well said. I can’t help but feel the “pain” of this problem. I was awarded the AMOCO teacher honor, served as president of the faculty senate for three years, chaired the North Central accreditation committee and the Review committee that ranked every subject area in the place, but, along with 90% of my colleagues had only one article published in our national journal. Add one textbook and a chapter in another, plus yearly handbooks in the argumentation area. Frankly, with chairing the senate, the department, two major university groups I had little time for anything more. Now you can see why I support the position you offered today.

I enjoyed reading this piece. I have wondered for some time why more attention is not given to teaching, especially since the students pay thousands of dollars for each class. I think putting too much weight on student reviews can be dangerous but it is definitely needs attention. In my 9 years teaching, the last 5 included the experience of having about 3-5 out of 20-25 students who were ill advised to stay in our major. I found the students who did poorly rated poorly. I also found an increasing number of students who did not want to read their books or complete long term projects. About 5-6 students in the class were curious, did their work and came to class asking questions. My class was more discussion and problem solving based than lecture based. The students wanted a power point and direction to what would be on the test. I did not give them that information and I am sure my ratings suferred. I did teach them how to create their own study guide. They did not want to be taught to fish. I think that is a reflection of our educational system today that trains them to pass the standardized tests that are taking over k-12 education. I was amazed that during my 9 years of teaching as a NTT that no faculty members ever stepped foot in my classroom or enquired about what/how I taught. I would have welcomes the opportunity. I think a peer review of teaching is an important piece that is missing for NTT faculty. Since so many still use the power point/talking head model for teaching, it is important that a variety of peers review the teaching. Based on my observations in classroms, the NTT faculty were more effective teachers than the TT faculty who either did not change with the times or who were focused on research and tenure, not on teaching. I also think having GAs doing the bulk of teaching is a huge disservice to students in many programs. They pay for the experienced professionals who are supposed to be good at what they do. I also observed the junk research ou mention. I was appalled at what I saw. It was especially horrifying that a professor could get away with editing his own peer reviewed journal and then fabricating peers who had no idea they were listed as peers. Pretty pathetic. Sure hope the climate changes for the better quickly for the sake of our nation.

There is so much pressure today upon the shoulders of those in the educational field. The work load can become seemingly unbearable when matched with so many other pressures. The pressures put upon GA’s should really be not only reflected upon, but drastically changed. GA’s must teach, grade, attend to their studies, and generally: publish. The pay for doing so much work is minimal. With the pressure and the lack of reward, it completely makes sense as to why so much garbage is being published. GA’s are pressured into completing loads of work for so little; it is obvious that the poor quality of work would be published.

Peer work is essential, however, who are the peers of the stressed, underpaid, and pressured GA’s? Those would be other stressed, underpaid, and pressured GA’s. Poor work being published is a reflection upon a system that seems to be more focused on quantity over quality. It is the reflection of a system that values names in the sea of publication over what is actually being published. Standards need to be raised and the focus of educational systems need to be more valued for quality over quantity.