Penned over a decade ago, but an element of truth persists.

Expectations, encouragement of them and their management are seeds of excellence.

In a New York Times piece on February 18, 2009, by Max Roosevelt entitled Student Expectations Seen as Causing Grade Disputes, James Hogge, associate dean of the Peabody School of Education at Vanderbilt University is quoted as: “Students often confuse the level of effort with the quality of work. There is a mentality in students that ‘if I work hard, I deserve a high grade.’” He’s right.

Philip Pirrip, or Pip, had modest ambitions by current standards. Charles Dickens’ protagonist Pip, in Great Expectations, wanted to be a blacksmith but ended up a gentleman. After a few years’ of apprenticeship under Joe Gargery, blacksmithing seemed “low” and “common”. Expectations rise faster than the price of gas. In a golden era long passed, or in the figment of our collective imagination, we were disappointed in ourselves for not meeting our expectations. Not so now.

Dashed expectations disappoint. The state, colleges, faculty, parents, brothers, sisters, latitude and longitude, in short our circumstances, but rarely ourselves, are cited as the cause.

President Obama said on February 24, 2009, “Tonight, I ask every American to commit to at least one year or more of higher education or career training. This can be community college or a four-year school; vocational training or an apprenticeship. But whatever the training may be, every American will need to get more than a high school diploma. …This country needs and values the talents of every American. That is why we will provide the support necessary for you to complete college and meet a new goal: by 2020, America will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.”

An inarguable and laudable goal that must change the face and nature of post-secondary education in our nation. Suggesting that “…every American to commit to at least one year or more of higher education or career training,” is one thing, but turning that into this new goal:…by 2020, America will once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world” is quite another. This rhetoric leads to confusion, not clarity, for students, parents, faculty, advisors, presidents and boards of trustees alike.

Not to say that expectations should be low, but I don’t think Pip’s were – all work has dignity – but not all work is for everybody.

Neal McCluskey, a Cato institute education fellow said “…39 percent–nearly two in five–of recent graduates who went to college after graduation said there were gaps in their high school preparation for the expectations of college.” He went on to suggest that “…only 24 percent of all surveyed high school graduates felt ‘they faced high academic expectations in high school and ‘were significantly challenged.’”

We sentence society to a slippery slope when we support students who suppose that average work is superior. We’ve convinced them that minimum effort is frugal, and therefore, virtuous.

Students themselves claim by an overwhelming majority that they would have worked harder had they been asked to – 80% of the high school graduates in one study. Why are we: parents, students, teachers, and educational leaders all afraid to tell the truth?

A willingness to work hard and a desire to be told the truth about effort and results seem lost expectations.

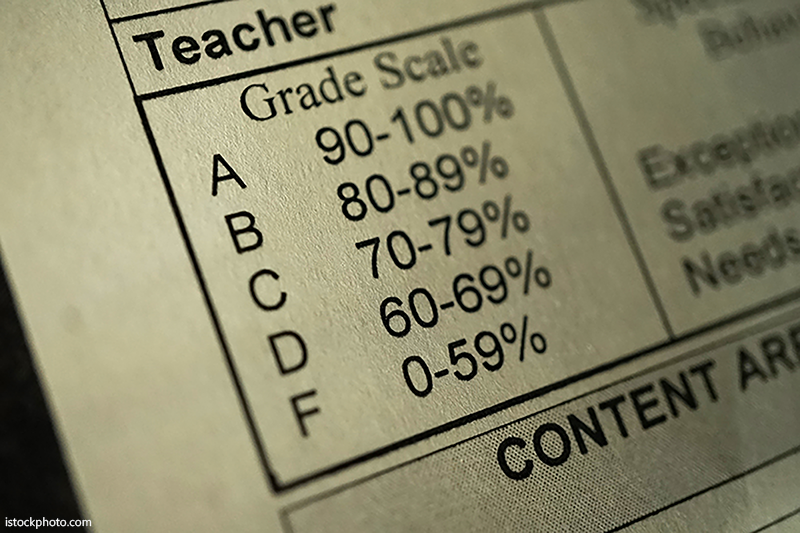

A student walked into my office three decades ago and asked, “Why did you give me a C.” I said, “I did not give you a ‘C’.” The student, with a look of relief on his face, said, “Oh, then there must be a recording error because I show that you gave me a ‘C’.” I said, “Oh, you are right; you have a ‘C’ recorded because you earned a ‘C’. If an ‘A’ or a ‘B’ was recorded, that would have been a mistake. I would have given you something you did not earn – a gift- but I didn’t give you anything. You worked hard, you were in class every day, you asked questions, and you acted interested. Those, not great but sincere expectations, are my expectations. You earned a ‘C’.”

“The grade reflects, to the best of my ability, an honest and fair assessment of what you earned for the work you performed: Do you want me to lie to you?”

He said, “Not really, but it would surely help my GPA.”

I thought to myself, “What a Pip.”

Walter V. Wendler, President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.