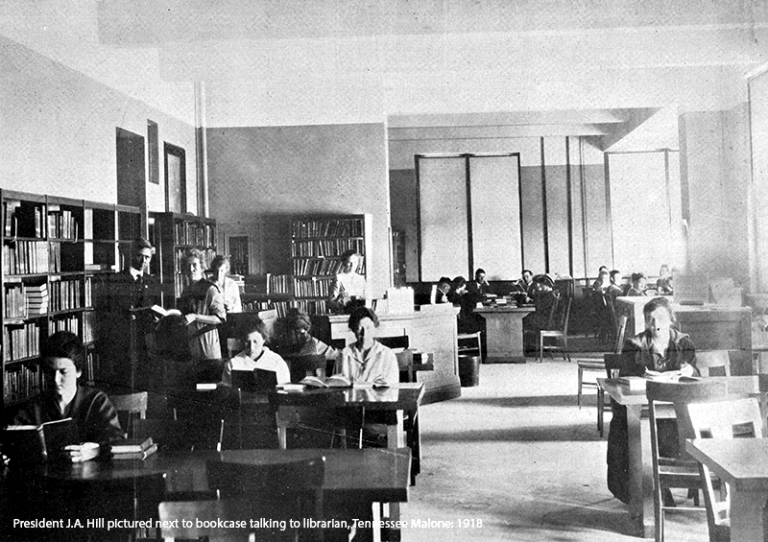

As schools open nationwide, it is worth reflecting on the impact of a college education. The Free Academy of New York, eventually City College of New York (CCNY) and City University of New York (CUNY) were created to provide a tuition-free education based on merit, not wealth, to the children of immigrants and the working class. CUNY’s motto says, “The education of free people is the hope of humanity.” Over 75% of the early students were the sons of poor and working-class families, particularly Jewish, Irish and other immigrant communities in New York City. While exact data from the 1840s is scarce, historians widely agree that a large majority, over 75% of early CCNY students, were first-generation college attendees. New York City’s leaders and students were tilling new soil.

The oldest siblings in a family may set a trajectory of accomplishment that marks a target for others to follow. They are a source of pride for parents and relatives, especially when engaged in a meaningful college experience combining moral acuity, intellectual excellence and vocational ability. Ten undergraduates from CCNY won the Nobel Prize, among the highest number of universities in America. Jonas Salk, who developed the first effective vaccine to prevent poliomyelitis (polio), helped eliminate the threat to the planet. Not a Nobel laureate, but he graduated from CCNY with a BS in chemistry in 1934. Resilient, resourceful and motivated, he was. Salk received an opportunity, not an entitlement. He produced ideas, not an ideology. Opportunity and ideas were, and are, the coin of the realm.

First-generation college students are rewriting the American Dream, often quietly, against long odds. Forbes reports that almost 56% of undergraduates in the United States are first-generation college students (community colleges have the highest percentages). This opportunity is not a rhetorical pronouncement but a lived experience. Yet, despite their growing presence and pivotal role in the nation’s civic fabric, they may be overlooked and their value underappreciated. Higher education policies and narratives should proclaim loudly the impact of first-in-family college attendance on family strength and economic development.

WT is working diligently to support these educational pioneers. Nearly 50% of our students are first-generation. F1RSTGEN: Support for First-Generation Students is an ambitious program to help first-generation students attain their academic aspirations through a carefully considered and thoughtfully executed college experience.

First-generation college students typically carry aspiration and promise. They often navigate complex academic and financial systems without the benefit of inherited parental and family guidance. Many are low-income students, like those who entered CCNY.

First-generation students face stark outcomes when compared to their continuing-generation peers. Nationally, only 24% of first-gen students complete their degree within four years compared to 59% of students whose parents have a college degree, according to First Gen Forward. The National Center for Education Statistics reports that the six-year graduation rate for first-generation students hovers around 50%, depending on institution type.

College graduates generally earn significantly more over their lifetimes than those with only a high school diploma. The Social Security Administration reports that they earn about $900,000 more. For first-in-family students, that income boost doesn’t just change individual lives, it transforms family trajectories and legacies while creating stronger communities.

The benefits are intergenerational, passed from one family member to another. Research reported by the Pew Research Center shows that the children of college graduates are more likely to attend and finish college themselves. First-generation graduates also have higher homeownership rates, civic engagement and retirement savings. According to the Lumina Foundation, they are more likely to vote, volunteer and participate in community leadership roles. All of these lead to a stronger economy and engaged citizenship supporting a constitutional republic.

Treating first-generation student support as a boutique concern is a mistake. These students should be a foundational commitment of every college and university. Being a first-generation student transcends political group identity. Such groups exist for power and influence, intellect, ability, merit, in a word. Heritage Foundation’s Education Freedom Report Card promotes educational choice and transparency. While not first-generation specific, these policies, such as education savings accounts, often benefit students who may lack family legacy or guidance as they traverse the college landscape.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. Institutions like West Texas A&M University, the University of California system, Florida International University and Texas A&M University–San Antonio have implemented successful scalable first-generation programs combining academic support, financial coaching and support initiatives according to NASPA.

In the polarized debates over who belongs in college, first-generation students are a powerful reminder of the purpose of education. They are not just climbing the ladder but building new rungs for everyone behind them. Their success is not a feel-good story; it is a measurable and structural investment in the country’s economic health, civic stability and social cohesion required to sustain a Republican form of government.

We cannot afford to ignore this student population if America is to live up to its promise of opportunity. First-generation students must be central to education policy and institutional frameworks, not the margins. They have already done the hard work of getting through the door. We must meet them with the tools and challenges to stay, succeed and soar.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.