National economic growth requires education beyond high school. College in the conventional sense is not always the answer to a stronger economy. Neither the traditional 20th century view of higher education from the student and family vantage point (outside looking in) that any college degree guarantees a job and a fulfilled life nor the institutional perch (inside looking out) that acculturating students is a valuable social service apart from imparting viable skills and capabilities will work. Both views are wrong-minded.

Thoughtful universities must change.

The academic staff at most universities used to be made up of a majority of faculty who were tenured and tenure-track and a minority of non-tenure-track or adjunct faculty with a focused commitment to teaching. According to the Association of Governing Boards of universities, in 1969 22% of the faculty members were non-tenure-track and 78% were in tenure-track positions. By 2009 the tables turned dramatically: Roughly 34% are permanent, and 66% are adjunct faculty, the equivalent of 21st century knowledge day-laborers.

This shift in hiring — driven by funding constraints and a shifting, possibly lost, focus — impacts every aspect of the university environment. Adjunct faculty fall into two groups. First, in the basic sciences and humanities, graduates who cannot find more permanent work and serve on a temporary basis teaching increasingly high numbers of core curriculum courses. They are powered by a love of teaching and study. Secondly, various practicing professionals bring the power of experience into the classroom as adjuncts. Both groups contribute to workforce readiness but neither may be fully valued in the institutional equation. Scarcity and morphing expectations demand new approaches. Business as usual works for a steadily decreasing piece of the educational pie.

According to the national conference of state legislatures, Community Colleges are preparing the workforce that will satisfy demand for 65% of all American jobs requiring some form of post-secondary education. The two-year schools are typically more nimble and willing to effectively prepare students for the marketplace armed with immediate employment utility.

Exacerbating this circumstance, many senior colleges don’t value job preparation and work-readiness as a serious part of a university education: It’s tolerated but seldom held up as high purpose. Critical thinking, the ability to write and use basic mathematical insights are all essential, but having a bachelor’s degree guarantees neither worker readiness, nor intellectual acuity. The emperor’s clothes are in a pile on the floor rather than in the closet. Nowhere is it written that the attainment of critical thinking ability undermines or diminishes a person’s capacity for the application of skills to solving a problem. However, it is “written” in the ancient Babylonian Talmud, “He who does not teach his son a trade teaches him as it were to rob” according to Rabbi Yehudah.

Reflective thinking and basic skills don’t peacefully coexist; they are interdependently joined at the hip. One without the other is impossible and effective workforce preparation requires both.

Recently, The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce published an overview of the economic value of college majors. The concept suggesting a college graduate will earn over a million dollars more in a professional lifetime than a non-college graduate is well worn. More pointedly, top paying college majors earned $3.4 million more than the lowest paying majors over equal professional lifetimes. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics affirms the disparity. It’s no mystery. Unfortunately, these realities are too rarely explained to students and families. As educational costs increase, informed choice in curriculum selection must also increase.

Decisive leadership on university campuses reduces statehouse oversight when effectiveness is evident. It’s currently not. A Governing the States and Localities report reveals just that. State houses darken school house doors in response to inaction on pressing issues. Crime, sexual assault, diminished tenure standards, graduation rates, and growing debt burdens demonstrate a lack of success in meeting legitimate social and economic needs. Not discounting the importance or legitimacy of any of these concerns is the overpowering public perception that a college degree is not as valuable in creating workforce readiness as it once was.

To relieve appropriate concerns curriculums that educate thinkers and train doers must be the result of every degree program. A stronger correlation between holding a degree and workforce readiness is a noble goal.

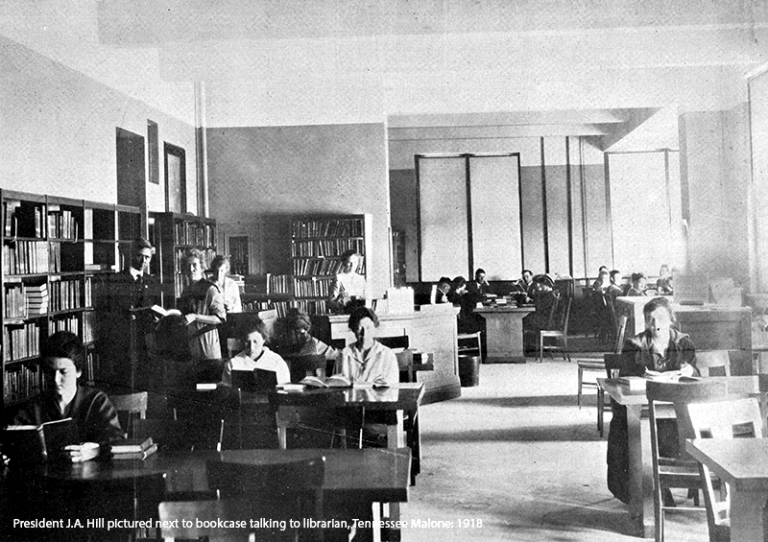

Image from sbefoundation.org