Flyover Country is where I live. This term is commonly used in the United States to refer to the central parts of our nation, especially the rural areas between the East and West coasts, you know, where all the “rednecks” live. The implication is that where I live is less significant or noteworthy than the coastal cities and is merely ‘flown over’ by travelers going between the coasts. You know, where all the “sophisticated” people live. A dismissive or pejorative connotation, to be sure, suggests that these areas are less culturally or economically important.

Such stereotyping overlooks the significant cultural, economic and social contributions of the heartland of our nation, its’ breadbasket, oil barrel and cotton bale that provides food, fuel and fiber for our entire country. Nobody is growing corn on Madison Avenue. You see very few cows in Houston’s River Oaks and nary a gas well or pump jack on Dallas’ West End.

The artifacts of the culture of my home are many: The Panhandle and numerous states and regions in the Midwest and Central U.S. are major agricultural producers, contributing significantly to both the national and global food supply. This includes crops like corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton and livestock. “Where’s the beef?” asked Democratic presidential primary candidate Walter Mondale of contender Gary Hart in 1984. That’s easy. He should have asked me: it’s in Hereford, Texas, and it ships beef to every state in the nation and nearly every continent on the globe.

States like Ohio, Michigan and Indiana are important in the automotive industry, while others have a significant presence in aerospace, machinery and food processing industries. Texas, Oklahoma and North Dakota are important for oil and natural gas production. Additionally, the Central U.S. is a leader in renewable energy, particularly wind power. While certain areas in flyover country have experienced robust economic growth, others face challenges such as population decline, job losses in certain sectors and the need for economic diversification.

Important as these observations may be in defining our national nucleus, they fall short of true regional genius. These places produce value systems that emulate the very best of our national founding—and shame on anyone who ignores the import of these values on our future.

Many areas in flyover country are deeply rooted in agriculture. Farming, ranching and industry produce a way of life. Community and family, close-knit relationships with neighbors and extended family, a strong sense of belonging and mutual support are all valued aspects of “life in the middle.” There is often a strong emphasis on traditional lifestyles, religious faith and a slower pace of life compared to the coastal cities. The region is known for its natural beauty, from the Great Plains to the rolling hills and rivers to the greatest canyon in the nation, Palo Duro Canyon, second only to the Grand Canyon. This region is not as monolithic as members of coastal tribes believe. Despite stereotypes, the region is home to a diverse range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. This diversity is reflected in local festivals, cuisine and community events. At one church in Amarillo, services every weekend are conducted in seven different languages.

People from flyover country often take great pride in their local identities, traditions and histories. They value their distinctiveness. The jewel in the crown is a nearly pervasive work ethic, self-reliance, personal responsibility and a relentless commitment to pragmatism. People in these regions are often noted for their hospitality and friendliness. There’s a sense of welcoming strangers and helping neighbors. Many people in flyover country have a deep connection to the land, whether through farming, hunting or simply a general appreciation of nature and the outdoors. There is often an appreciation for a simpler, more straightforward way of life, with less emphasis on materialism and more on practical, functional living. A strong sense of patriotism and pride in our country is sometimes expressed more openly than in other regions.

These facets of national life were cut into the steel of the Industrial Revolution through the Morrill Act of 1862, signed by President Lincoln on July 2. This landmark legislation, named after its sponsor, Vermont Congressman Justin Smith Morrill, aimed to expand access to higher education. The A and M of the land-grant institutions represented the very fabric of the heartland of our nation, “agriculture and the mechanic arts,” as an alternative to the classical studies offered by existing colleges. It was a response to industrialization and more openly accessible learning possibilities for working classes: An educational opportunity that emphasized practical skills and a departure from the traditional university experience.

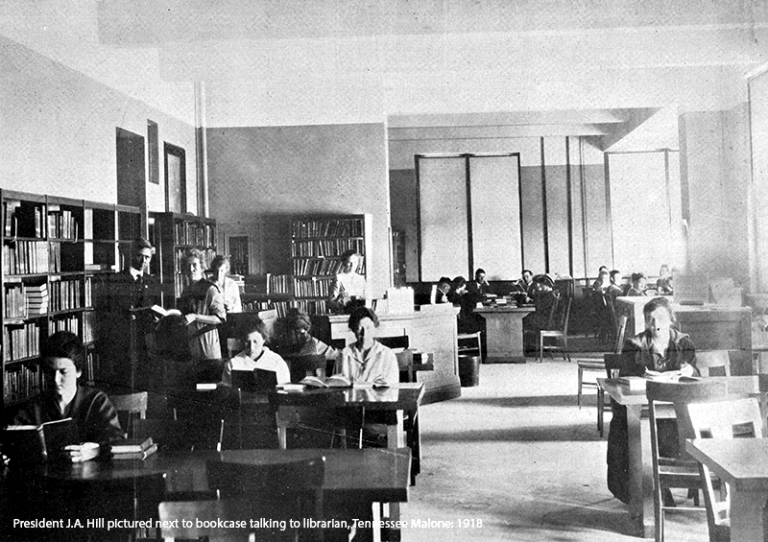

The establishment of land-grant universities fundamentally transformed American higher education by creating access and emphasizing practical, vocational and technical education. These institutions played a crucial role, pivotal in research, innovation and community service. While West Texas A&M University is not a land-grant university, many in our region aspire to sustain the values of flyover country because they had great power at the height of the Civil War and still have great power in transforming a region and a nation and sustaining a republican form of government. The effort at West Texas A&M University to create engaged citizens is a reflection of academic progress in the 21st century and a potent example of our values at work.

We forget this progress at our peril.

Walter V. Wendler, President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.