The history of shared governance in universities is long and layered, rooted in medieval traditions and evolving through American higher education. The earliest universities, such as Bologna and Paris, were communities where professors and students formed guilds, electing directors and making decisions collectively. Over time, monarchs and the Church exerted more control, but the ideal of the university as a self-governing body of scholars remained influential. Colonial colleges (e.g., Harvard, Yale, Princeton) were modeled partly on Oxford and Cambridge but primarily governed by boards of trustees, often dominated by clergy. Faculty had little formal role in governance and running the university. Trustees and presidents exercised the authority of governing. The dynamic tension between external control (trustees) and the internal academic community (faculty) has a long history.

German universities influenced American higher education by emphasizing academic freedom, making professors central to governance. As American universities rapidly expanded, faculty senates began forming to provide a collective voice to influence governance. Still, power often resided with presidents and trustees, reflecting a corporate-style organization. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP), founded in 1915, became a key advocate for shared governance. In the 1920s–30s, faculty senates became more common, institutionalizing faculty participation in academic decisions. In the 1960s–70s, faculty shared governance was tested by financial pressures, unionization and student activism. By the 1980s–90s, many universities institutionalized faculty senates and committees as permanent parts of governance. Shared governance has increasingly expanded to include students and staff in advisory roles. Pressures of corporatization, financial crises and growing administrative layers have strained shared governance. Many faculty argue that trustees and administrations have centralized authority, particularly in budget, strategic planning and program decisions. At the same time, shared governance remains a touchstone principle, often invoked in disputes over academic freedom, tenure and institutional change.

Universities are not alone in taking input from all corners of the organization. Toyota’s lean manufacturing model explicitly empowers line workers to stop production if they detect a problem (Andon cord). This distributes quality control into a shared world of frontline workers and leaders, making each a more active decision-maker, rather than a passive executor. Jeffrey Liker’s “The Toyota Way” argues the practice “ensures that problem-solving is shared between workers and management, embedding continuous improvement (kaizen) into governance.” In the 1960s–70s, Toyota institutionalized quality circles: small groups of workers meet regularly to identify problems, propose solutions and implement improvements. These groups became a shared governance mechanism giving workers real input into operations, safety and efficiency. Western manufacturers widely studied and copied Toyota quality circles in the 1980s. Toyota’s version of shared governance lives in quality circles, shop-floor empowerment, shared decision-making and supplier partnerships. Building cars and providing individually defined educational opportunities for students at a public university are not the same, but shared leadership concepts have significant similarities.

However, correctly configured faculty senates are based on the same principle: those closest to the educational mission share insights and ideas with leadership. At their core, Toyota and universities embrace the principle that those closest to the work are authorities whose counsel should be sought. Both empower and entrust those doing the core work, whether factory workers or faculty, to impact quality and make purposeful decisions. Sharing leadership toward attaining the institutional mission prioritizes deliberative processes and outcomes.

While Toyota emphasizes efficiency and feedback loops that produce rapid operational adjustments, university shared governance, in contrast, often moves slowly due to deliberate norms and tenure protections. Product and purpose are central to Toyota’s production excellence and market performance goals. Universities balance economic, civic and intellectual aims, which can complicate governance and bring moderately conservative responses to change, maintaining significant cultural forces within the organization and its purposes.

Comparing Toyota and universities reveals that shared governance is a flexible principle, adaptable across sectors, but shaped by the institution’s mission, culture and external pressures. Highlighting this comparison could help universities rethink the purpose and process of shared governance in light of operational excellence and collaborative culture, as Toyota has done.

The CEO has a distinctive role in both universities and corporate production settings. In shared governance systems, CEOs do not micromanage every decision. Instead, they set broad visions and goals, while frontline employees, councils or trustees share authority over how to achieve them. At Toyota, the CEO articulates a long-term philosophy such as quality, continuous improvement and respect for people. However, the “how” is influenced by kaizen teams, quality circles and shop-floor authority. CEOs act as boundary managers. Shared governance only works if the culture supports it. CEOs function as guardians of values. At Toyota, continuous improvement and respect for people are the focus values; the same should be true in universities.

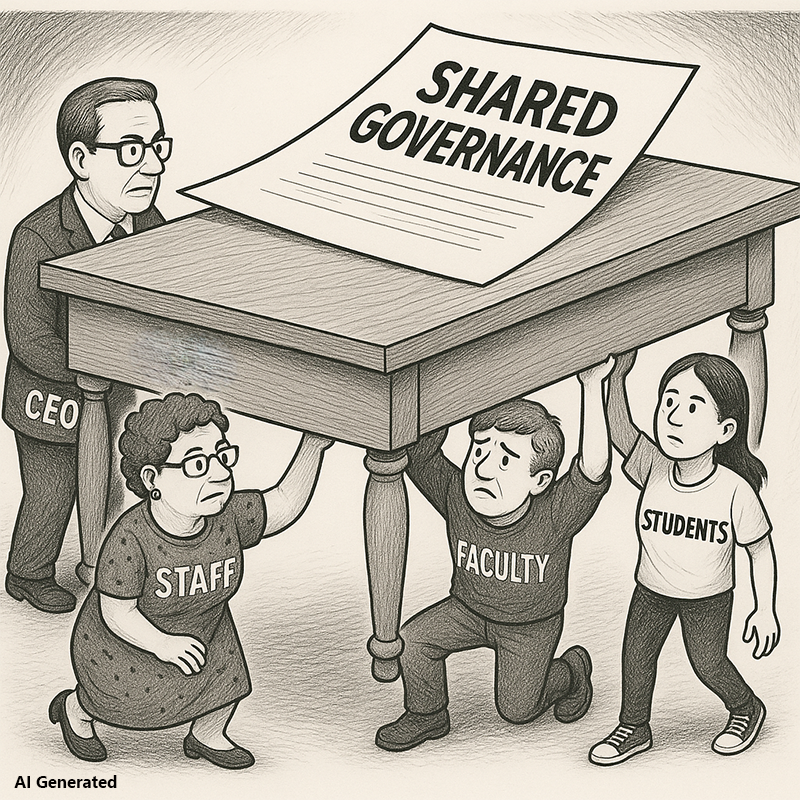

CEOs hold final accountability in both settings, which is the central leadership responsibility in any setting. Even in shared governance environments, CEOs remain accountable for outcomes. Accountability cannot be transferred or given to committees. CEOs may share decision-making but are ultimately responsible for performance, compliance and long-term survival. Therein lies a paradox: authority is shared, but accountability is concentrated.

Recommendations and suggestions in any shared governance environment are just that, recommendations and suggestions. Ultimately, the CEO is responsible. As President Truman said, “The buck stops here.”

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.