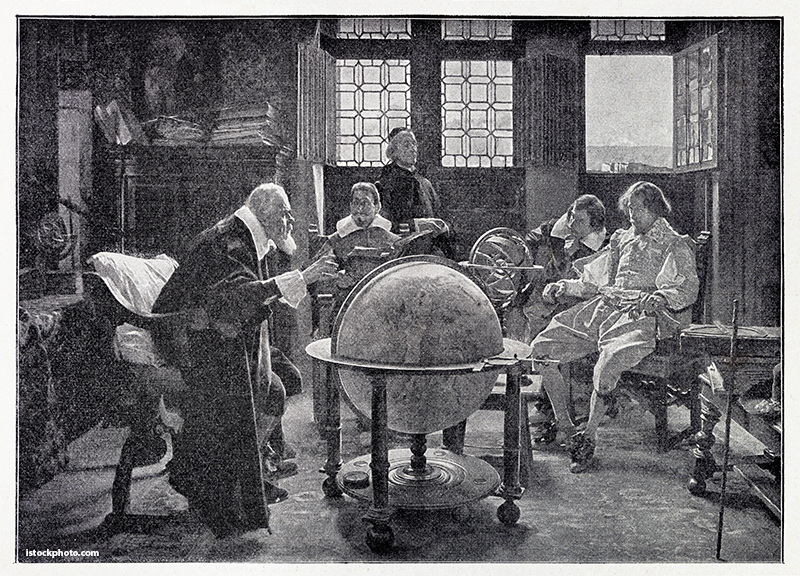

While teaching geometry, mechanics and astronomy at the University of Padua, Galileo studied the movements of the Sun and the stars, and through his personal observations, proposed that our universe was heliocentric. His ideas and findings supported Copernicus’s repudiation of the geocentric view of the universe. Galileo had no tenure, no safety net and no bureaucracy, relying solely on pure scholarship.

Tenure’s strength lies not in comfort but in courage, and courage fails when sinecure of any kind protects people. Tenure is soul-stealing. The word sinecure comes from the Latin sine cura, meaning “without care.” That phrase should chill every scholar. A scholar’s stock-in-trade is diligent, procedural, truthful, peer-reviewed care. A tenured professor not guided by restless curiosity that drives discovery, without the circumspect courage to dissent, renders tenure hollow. That may be our present state in too many instances. A safeguard for speaking and publishing ideas that are not the result of personal study and mastery is not a substitute for courage and intellectual accomplishment; it is a sinecure. Galileo’s ideas were guided by a careful process and subjected to the review of his scholarly peers in the field of inquiry. He was a slave to neither ideology of orthodoxy, but to reason and observation, to study.

When Galileo was summoned before the Roman Inquisition in 1633, he faced not a panel of scientists but a tribunal of power. The Inquisition found him “vehemently suspect of heresy.” He was not accused of fraud, deceit or academic misconduct. His crime was self-directed, passionate curiosity. Discovery. Ideas. All bound together by an unwillingness to let dogma define what his own eyes and instruments revealed. Through his telescope, he observed the moons of Jupiter and the phases of Venus, each turning the old Earth-centered universe on its head. For that, he was forced to kneel and recant his words. “And yet it moves,” (Eppur si muove), he is said to have murmured under his breath. A quiet rebellion in defense of truth.

The church rejected his science, labeling it heresy. His heliocentric view of the universe contradicted the biblical perspective based on a few verses of scripture, notably Psalm 104:5: “He set the earth on its foundations; it can never be moved.” Ecclesiastes 1:5: “The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises.” Joshua 10:12-3: Joshua commands the Sun to stand still in the sky so Israel can win a battle, implying the Sun moves around the Earth. Fragmentation of Holy Writ to meet human perception is nearly always ill-considered. Galileo said, “The intention of the Holy Spirit is to teach us how one goes to heaven, not how the heavens go.”

Tenure is the jewel in the crown of academic freedom, protecting scholars from political and institutional interference or retaliation. But the reality is more complicated. Even with modern tenure, Galileo’s safety might have been uncertain. Moreover, very few people in their field of expertise have ideas that are both provocative and powerful enough to unseat orthodoxy. I have seen it only once in 50 years of university life.

Founded in church, state or academic community, orthodoxy is orthodoxy. Adopting others’ ideas that oppose orthodoxy is a matter of politics, not scholarship. Choosing one perspective over another is a matter of ideology. We may be transforming tenure into a form of costume jewelry, not the gemstone of academic freedom.

Confusing tenure and its parent, academic freedom, with First Amendment protections diminishes the value of both; tenure is earned through peer evaluation and review. First Amendment protections are given to every citizen in our country at birth. The question, then, is not whether tenure would have saved Galileo’s job, but whether it would have strengthened the spirit of independent thought that led him to the house arrest he endured. Tenure would have mattered, not as a legal shield, but as a moral signal. It would have declared that the pursuit of truth transcends orthodoxy and that honest inquiry deserves protection, even when unsettling, but only as the product of personal study and ideation, not groupthink or birthright constitutional protections.

Tenure was never meant to guarantee ease or shield one from scrutiny, but to promote examination by scholars who also value understanding their disciplines. Tenure was designed to ensure the freedom to challenge and be challenged. The scholar’s privilege comes with a duty: to pursue truth rigorously, teach it humbly and defend it courageously. When tenure turns into a hammock rather than a harness, the academy forgets its moral obligation to the public. Galileo’s courage teaches us to seek truth, not safety. His life and work testify that intellectual freedom is not a reward but a responsibility.

Tenure, rightly understood, is not a relic of privilege, but a living covenant between the university and the public it serves through its individual members. Scholarly expertise galvanized by peers must constrain that freedom for the common good. Without those qualifications, tenure becomes either license or liability, an entitlement without energy or a shield without courage.

Galileo’s story endures because the struggle between knowledge and orthodoxy endures. Every age has its sacred certainties, and every age produces those who dare to look through the telescope and see otherwise. The lesson is not that we need more Galileos, but that universities need leadership willing to protect those who generate ideas through rigorous scholarship, not those who weld themselves to ideology or orthodoxy of any stripe.

In the end, the question “Did Galileo need tenure?” leads to a more significant one: “Do modern scholars use tenure to do what Galileo did?” If the answer is yes, tenure remains one of civilization’s finest inventions—a social contract that honors inquiry, integrity and courage. If the answer is no, then tenure risks becoming little more than decoration, a sinecure without curiosity, without care and without truth.

Freedom of thought is never finally secured. It must be defended, exercised and renewed again and again, as fiercely as Galileo defended what he saw through his lens. New ideas are never an entitlement or a trinket. Universities should value ideas pursued with passion and rigor as the work of the scholar. High-minded? No, it is the bedrock of teaching and learning, and should be treated with great care.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.