First in a Series.

American higher education once rested on a shared moral vision shaped by Judeo-Christian traditions, affirming the dignity of every person. These moral responsibilities accompany freedom and the pursuit of truth as a sacred calling. George Marsden argued in The Soul of the American University, “The source of our strength in the quest for human freedom is not material but spiritual, and because it knows no limitation, it must terrify and ultimately triumph over those who would enslave their souls.” Over the past century, the spiritual foundation of education has eroded. Universities have mastered the production of knowledge, often at the neglect of cultivating wisdom and character.

Judeo-Christian principles—not as sectarian doctrine, but as the moral heritage of Western liberty—may be the key to restoring coherence, purpose and public trust to higher education.

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, American colleges combined intellect and virtue. Harvard, Yale and Princeton were founded to form leaders who could unite faith and reason. Even the land-grant universities created by the Morrill Act of 1862 retained a civic ethic rooted in religious moral philosophy: industriousness, honesty and service.

From the beginning, universities recognized that moral education was central to their public mission. Things like chapel services and courses in moral philosophy reinforced the conviction that truth existed and that freedom required restraint.

By the late 19th century, however, the research ideal imported from Germany transformed universities into professional and technical institutions. The rise of scientific positivism and the secular interpretation of the First Amendment encouraged moral, thus religious, neutrality. Court decisions such as Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Everson v. Board of Education (1947) defined religion as a private matter separate from public or state matters. In the process, higher education lost the vocabulary of virtue and the benefit of theology.

As I observed in Universities and Moral Duty in a Republic, “For them, (The Founders) the republic’s survival depended on moral, civic and formative education. They knew liberty without virtue collapses into license and democracy without moral formation disintegrates into disorder.”

Reintroducing Judeo-Christian values into higher education does not require the establishment of religion. The Supreme Court has long held that studying the influence of religion on history and culture is constitutional (Abington School District v. Schempp, 1963). To teach that the ideas of liberty and justice have religious roots is an act of honesty, not indoctrination.

In Faith on the University Campus, I wrote that, “One of the failings of contemporary universities is that they nearly insist on a separation of spiritual and intellectual life, faith and reason.” A constitutional republic cannot endure without citizens capable of moral judgment. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “Liberty cannot be established without morality, nor morality without faith.”

Public universities would do well to recommit to recognizing that their civic mission, which involves preparing responsible citizens, depends on moral formation. Students must learn not only how to make a living but how to live. The university is not the only place where students should learn how to live, but it certainly should not be a place devoid of moral teaching and mentoring. Leadership in higher education can restore moral coherence by reaffirming that education forms both character and intellect. Mission statements should commit to truth, integrity, service and respect for the inherent worth of every person—virtues with a deep Judeo-Christian lineage. Run straight at it, not away from it.

A revitalized core curriculum could unite knowledge and ethics. Great texts and moral reasoning courses can place theological, classical and modern works in conversation. Professional programs can integrate moral reflection into their curricula, such as stewardship in business, compassion in medicine, justice in law and human dignity in engineering.

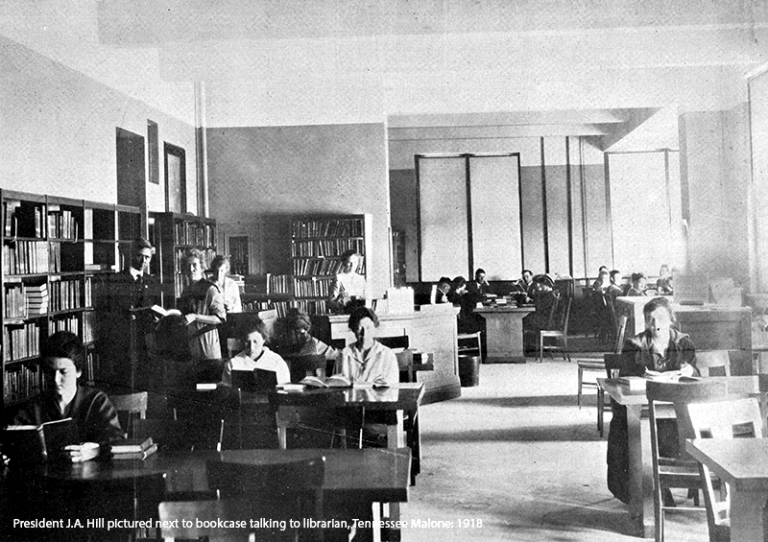

Universities might create centers and institutes to reintroduce moral teaching and reflection by hosting teaching, research and service programs, as well as recognizing faculty who incorporate values into their scholarly work. The Hill Institute at WT “…seeks to reflect on the importance and power of individual responsibility, personal choice and the exercise of free moral agency. As defining characteristics of all people in a truly free society, no matter the circumstances of life, these give rise to a fundamental form of equality that should bind us all together.” These characteristics are foundational to everyone, regardless of their walk of life or belief system.

Faith-based student organizations and faculty members should enjoy full freedom of expression. Viewpoint neutrality requires not the suppression of moral reasoning but the inclusion of diverse perspectives, both religious and secular. Collaboration with local congregations, synagogues and civic organizations can connect moral ideas to public action. Service-learning projects grounded in compassion and stewardship embody the university’s role as servant to society.

Reintroducing Judeo-Christian principles brings the hope of reconnecting intellectual inquiry with ethical purpose, cultivating graduates who unite competence with conscience, rebuilding civic trust in higher education as a formative enterprise rather than merely a technical one and advancing pluralism based on shared moral seriousness rather than ideological uniformity. These outcomes could help renew universities as communities devoted to truth and ordered liberty.

The call to restore Judeo-Christian values is not a call for theocracy but for integrity. Freedom without virtue decays into license. Education without moral direction becomes sterile expertise.

Public universities should again teach that truth exists, that moral responsibility accompanies freedom and that knowledge should serve both God and neighbor. As I wrote in Private and Civic Virtue, “…the greatest threats to a nation’s sustenance and security may come from within rather than without. When self-service guides all decision-making, citizenship takes a backseat to narcissism.” When universities educate for character as well as competence, higher education strengthens the very fabric of the republic.

Reclaiming moral purpose will not divide campuses—it could heal them. By acknowledging the moral sources of our liberty, higher education can renew its calling as the conscience of the nation and the servant of its people.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.