Fourth in a series.

Universities do not exist to produce intellectual unanimity; they exist to cultivate free minds capable of wrestling with complex truths. But freedom of thought is impossible without freedom of conscience. The ability of every person to believe, question, dissent and stand firm without fear of punishment is primary. This is not an ornament in higher education; it is the foundation, and it is cracking.

Across campuses nationwide, conformity is too often demanded. Dominant ideologies are sometimes political, cultural or institutional, and sometimes emerge from faculty groups or establish orthodoxies; they may be openly ideological, as in George Orwell’s work, or cloaked as high-mindedness. Students and faculty quickly learn which opinions are “safe” and which are not. The result is not education, but indoctrination dressed up in strong academic regalia.

The Western tradition offers an antidote which begins with a simple truth: conscience must remain free. The Judeo-Christian tradition makes this point with remarkable clarity. The Apostle Paul, writing to early Christians in Rome, urges them not to coerce one another into uniformity. Instead, he insists that each person “be fully convinced in his own mind.” In matters of belief, Paul argues, coercion is both fruitless and immoral. The responsibility for conviction rests with the individual, not the group, in the civil exercise of free will. Groupthink did not work in George Orwell’s 1984, and it doesn’t now.

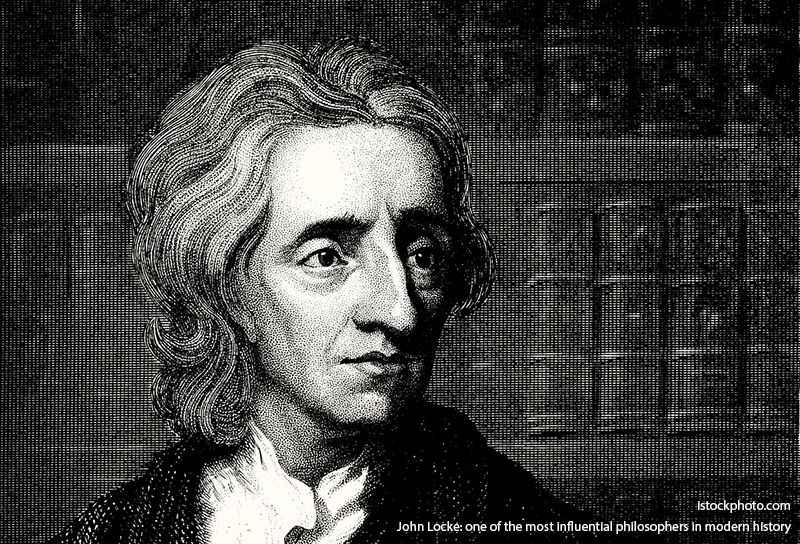

The principle of conviction shaped centuries of thought and directly influenced those who helped build the intellectual DNA of the modern university. John Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration declared that the state has no authority to force belief, because compelled belief is not belief at all. You cannot legislate conviction; you can only bully people into silence. Roger Williams echoed the same warning in The Bloody Tenet of Persecution, arguing that punishing heretics violates both conscience and being created in the image of God. These thinkers were not merely defending religious liberty; they were defending the conditions necessary for honest inquiry. Their insights were the early blueprints of what we now call academic freedom, never to be confused with free speech.

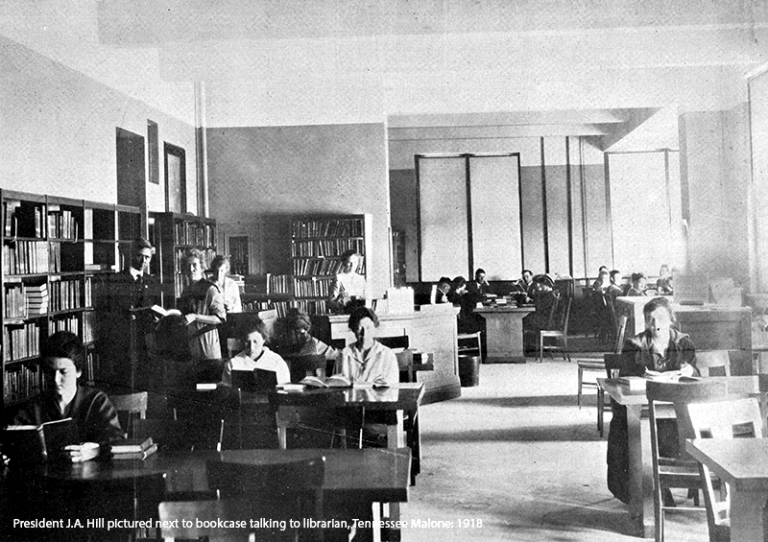

And yet, contemporary universities behave as though they can divorce the intellect from the conscience, or faith from reason. It is as though students can be asked to think courageously while being told to put their deepest beliefs in a bucket at the campus gate. I reminded our students, faculty and staff in 2009: “Do not check your faith at the campus gate.” Asking people to amputate their convictions before entering a classroom is not intellectual neutrality; it is intellectual mutilation.

The human mind does not operate in separate compartments labeled “reason” and “belief.” We are whole persons. Our moral commitments and our intellectual pursuits shape one another. Pretending otherwise does not elevate discourse; it starves it to death.

Because we are whole persons, freedom of conscience is indispensable to intellectual diversity. When individuals feel pressured to adopt fashionable viewpoints or conceal unpopular ones, genuine learning collapses, discussion becomes a performance, inquiry becomes obedience and ideas are no longer tested; they are enforced.

And enforcement of ideas has consequences. Students who fear social or academic retribution do not speak. Faculty who worry about professional repercussions do not research controversial questions. Administrators who care more about avoiding criticism than pursuing truth capitulate to the loudest voices. In such an environment, the search for truth, which is the core purpose of the university, dies quietly.

The pressure to conform also undermines humility, a virtue without which no intellectual community can thrive. Civility is the child of humility. Saint Paul famously reminds us that we “see through a glass, darkly.” Recognizing our own limitations is what allows us to listen, reconsider and grow; it is what gives disagreement value. When someone challenges our assumptions, they are offering us a gift, an opportunity to see more clearly.

This is why I hold, and have written before, that toleration and conviction are not enemies; they are partners. Toleration demands we listen with respect. Conviction demands we speak with honesty. A campus that cannot do both is not cultivating thinkers; it is manufacturing echo chambers.

The stakes could not be higher. Universities claim to be guardians of truth, yet truth cannot be guarded by coercion. Truth emerges only when ideas are tested, refined, challenged and debated. Institutions that silence civil dissent, whether through formal policies or informal pressures, sacrifice their legitimacy. They become ideological instruments rather than intellectual irons in the fires of free thought.

The Judeo-Christian defense of conscience is not an attempt to impose belief on universities. It serves as a reminder that any belief, no matter how strong, cannot be imposed upon others. Judeo-Christian tradition, as I understand it, does not seek to control thought, but to free it by teaching that every person bears both the right and the responsibility to search for truth without interference.

Our society desperately needs universities willing to defend that freedom. We need campuses where civil disagreement is treated not as a threat but as evidence of vitality. We need educators who understand that students grow not by memorizing the “orthodoxy of the moment” but by confronting competing ideas with courage and humility. And we need leaders willing to protect conscience even when doing so is unpopular.

Without freedom of conscience, intellectual diversity becomes a slogan without substance, and inquiry stagnates, learning becomes a hollow ritual, and thus only ideology remains.

But with freedom of conscience, guarded, honored and practiced, the university becomes what it was meant to be: a community devoted to truth, strengthened by difference and animated by the dignity of every person who seeks to learn. Students deserve to see these principles at work. At WT, it is what students pay for.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns are available at https://walterwendler.com/.