Third in a series.

In American higher education, freedom is often a flag flown high; freedom of inquiry, thought and speech are indispensable to the life of the mind. Yet, as I have seen across decades in the academy, freedom standing alone is an unsure foundation of anything except temporal or intellectual excitement, satisfaction or pleasure. Unmoored from the taproot of responsibility expressed in the Judeo-Christian tradition, freedom quickly collapses into license and self-interest. True academic excellence is dangerous without virtue. Freedom and responsibility are two sides of the same coin—one cannot be sustained without the other.

The Apostle Paul cautioned in his letter to the Gentiles in Galatia not to allow their newly received freedom to misguide their actions. He said in 5:13, “You were called to be free… only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh.” While some may object to citing a religious text, it could be extended to a broader, non-religious perspective with a simple amendment: You were called to freedom… but it is not for you, yourself; your freedom is for the benefit of others. This ancient admonition rings true today. Freedom is not a license for self-indulgence or domination, but a call to serve others, to love and to steward one’s gifts for the common good. That is how our “Western Tradition” has rooted freedom in responsibility. Academic freedom, so dearly prized, is not given for its own sake but entrusted to faculty and students as a moral obligation. At its best, freedom is not an opportunity to pursue truth for mere personal gain, but for a larger purpose manifested in its benefit to and for others. Self-serving academic freedom is poor scholarship.

Historically, Marx overlooks several key points, largely due to the profound impact of the Industrial Revolution and the significant changes in the distribution of labor and capital. Capitalism did not collapse from internal contradictions, even in its imperfections. The living standards of many, but not all, rose; they did not fall. Revolutions happened in less industrialized countries (Russia, China), as Marx expected. The middle class typically expanded rather than disappeared.

Reinhold Niebuhr, an observer of human nature, recognized our moral vulnerability in The Nature and Destiny of Man. We are capable of great creativity, but also distortion and self-deception. Freedom, to be authentic, must be disciplined by humility and a clear-eyed sense of our own limitations and responsibility. In the halls of the university, whether in research, teaching or public engagement, freedom without virtue leads to harm. Intellectual power, if untethered from honesty, humility and accountability, becomes a dangerous tool for manipulation rather than a means of enlightenment. History has repeatedly shown that enticing ideas, unfettered by a moral calculus and driven solely by ideology, often lead to outcomes that do not serve or empower people. What starts with good intentions meanders into something that works against the individual’s personal fulfillment and the greater good.

John Henry Newman, in The Idea of a University, insisted that intellectual virtue is inseparable from the freedom to inquire. The scholar’s task is not merely to seek knowledge but to do so with fairness, integrity and devotion to truth rooted in a greater purpose. In our era, when misinformation and ideological pressure threaten both the classroom and the research enterprise, Newman’s warning bears repeating: freedom without virtue invites error, undermines trust and corrodes the soul of the university.

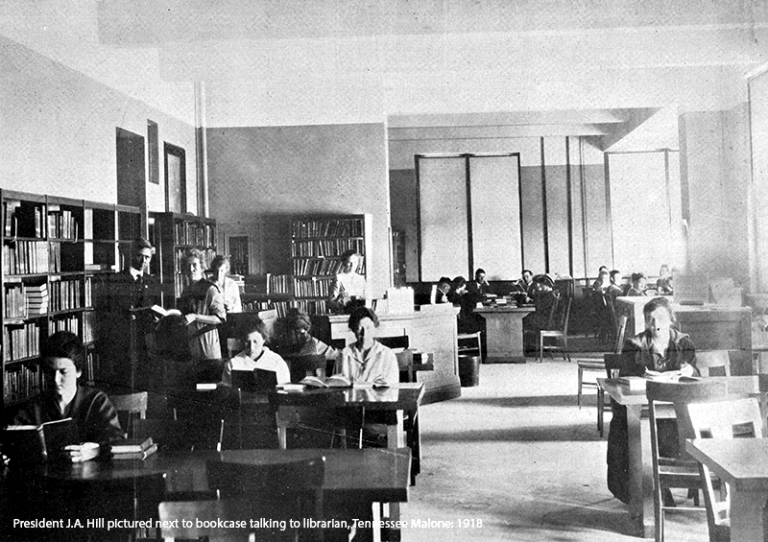

The Judeo-Christian tradition teaches that responsibility flows from conscience. It is the nature of our free will. Paul’s letters to Galatia urge us to be governed by an inner witness to a greater form of freedom, not merely external rules. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn observed in The Gulag Archipelago: “The line separating good and evil passes…right through every human heart.” I agree. At West Texas A&M University, I have seen Solzhenitsyn’s principle come to life when policies are animated by character, truthfulness, fairness, diligence and concern for others. No code or regulation can substitute for the virtues of those who live out academic freedom.

What, then, does responsible academic freedom require?

First, unwavering intellectual honesty. Research must reflect reality, not ideology. The ancient commandment, “Thou shalt not bear false witness,” reminds us that truthfulness is not optional; it is the very heart of careful Western thought and the academic mission.

Second, the rejection of indoctrination. The classroom must be a place where students are invited to think, question and judge for themselves. The teacher Augustine admitted his own errors and encouraged continual self-examination. Genuine persuasion appeals to reason and conscience, not coercion. Science and knowledge exist free from ideology, especially religious ideology. Robert Merton in The Normative Structure of Science wrote, “The institutional goal of science is the extension of certified knowledge…The purity of science is maintained by the imperative of disinterestedness.”

And third, responsible academic freedom requires disciplined integrity. Freedom to pursue challenging questions must be matched by rigorous methods and respect for disciplinary standards. Aquinas taught that habits of clarity and logic are essential to intellectual virtue—virtues which protect scholarship from devolving into spectacle or partisanship.

When responsibility is neglected, freedom becomes destructive and public trust in universities erodes; students lose agency, and knowledge itself becomes suspect. However, when freedom and responsibility walk hand in hand, the university flourishes, serving as a beacon of truth, a cultivator of wisdom and a force for the common good.

The marriage of freedom and responsibility is not just an inheritance of Judeo-Christian thought, but a necessary foundation for the future of higher education. Paul’s warning, Marx’s ideas, Newman’s vision and Niebuhr’s realism all converge by insisting that academic freedom requires disciplined integrity. Without responsibility, freedom destroys itself. Together, liberty and responsibility enable the university to achieve its highest purpose, forming individuals of character, conviction and service.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.