Fifth in a series.

One of the most profound gifts of the Judeo-Christian tradition to Western civilization is its steady skepticism toward concentrated power. That suspicion is not a historical ornament; it remains essential to the health of humanity and universities. More than ten years ago, I cautioned that universities cannot rely on borrowed moral authority; morals must originate within the academy. I still believe healthy skepticism about university power cannot be injected from the outside, such skepticism has to grow from within from the people who teach, study and work in the institution. At times, the moral backbone feels flimsy, even though healthy skepticism strengthens the university’s purpose.

Abraham Kuyper, in his 1898 Lectures on Calvinism at Princeton, argued that each sphere of life, the church, state and university, must guard its independence. His emphasis on boundaries echoes the separation of powers at the heart of free societies. Today, though, the discipline required to keep those boundaries intact seems to be bending. University presidents, often principled and hardworking, can find themselves eased along by bureaucratic behaviors instead of resisting when conscience demands more backbone. Standing still in a current takes effort, and we forget that at the peril of the enterprise. Likewise, presidents who are above critique or unwilling to seek advice, regardless of whether the advice is followed, become so rigid they themselves do not recognize the boundaries of their powers.

The biblical account of Exodus makes the point. Pharaoh serves as the classic example of tyranny; the divine call for liberation pushes back against illegitimate authority. I have argued that the narrative is a profound political statement about illegitimate, unaccountable power contradicting divine justice. Power, whether political, religious or cultural, requires ethical limits. The Hebrew prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Amos never stopped warning people that when leaders grip too tightly, when honest speech dries up the life of a community slumps.

Christian thinkers inherited and expanded this concern. Augustine, in The City of God, saw political authority as necessary but fragile and believed it must remain “humble, restrained and accountable.” Aquinas, in Summa Theologica, sharpened the definition: “An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law.” Centuries later, Martin Luther King, Jr., writing in A Letter from a Birmingham Jail, echoed Aquinas in arguing that institutions separated from deeper standards lose legitimacy. Although these leaders lived in different times and faced different theological questions, they shared an insistence that power must answer to something greater than itself.

The ideas of Augustine, Aquinas and Martin Luther King, Jr. matter in academic life. Tenure, properly understood, is not a reward but a safeguard, protecting scholars from both external influence and internal pressure, allowing them to pursue their studies to their fullest conclusions. Tenure is, too often, inappropriately viewed as a form of free speech. It is not free speech, but an intellectual expression of “the right to work.” Two very different concepts. Free speech allows a voice to be coupled with a constitutional provision. Tenure requires scholarly expertise and professional academic responsibility. The goal is simple: scholars must be free to civilly follow the truth, wherever their field of study leads.

Threats to tenure do not come solely from external forces. Increasingly, threats to pursue one’s field are growing within universities themselves. Intellectual conformity, or imprisonment, can take hold quietly, almost unnoticed. Hannah Arendt, through her concept of the “Banality of Evil,” warned how people can slip into agreement because dissent feels awkward or risky. When a campus begins to suggest which views are “expected subtly,” it loses something vital. The desire for tenure has often silenced, either unknowingly or willingly, those seeking it, resulting in conformity.

Ayn Rand, writing from a different tradition, recognized the importance of individual rights, arguing that an individualist respects both his own rights and those of others. There is a growing greed for rights unattached to responsibilities, in the form of an often sanctimonious demand to be heard. Let truth adjust the volume of the expression of thought. Whatever one thinks of Rand’s broader philosophy, truth-seeking requires space for quiet, rigorous and thoughtful disagreement.

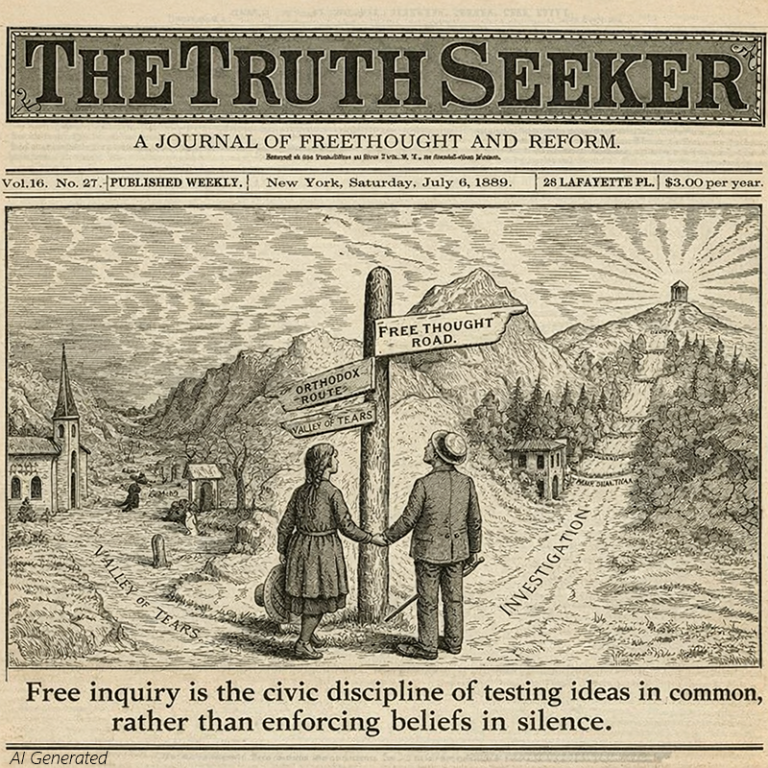

At their best, American universities show “institutional courage” defined by a willingness to defend the conditions that make open inquiry possible. How? By resisting undue external influence and resisting the inexorable internal tendency toward sameness of thought. In 2016, I wrote in Freedom for, or from, Ideas that “Freedom of speech is a birthright and the heart of citizenship. In contrast, academic freedom is earned, never given.” Academic freedom is the heart and soul of scholarship. Universities must cultivate habits of mind that welcome debate, tolerate friction and push back against pressures limiting intellectual exploration.

Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, argued that institutions survive only when anchored by firm moral principles, and moral principles should be openly and civilly discussed within the institution. When a university drifts away from those principles, even slightly, it begins to serve the interests of influence rather than the pursuit of truth.

The Judeo-Christian suspicion of tyranny and anarchy is more than a theological memory or fascination; it is a cultural resource that can strengthen higher education. The most reliable resource for a strong university is the civil intellectual resilience of the people within. I argued previously in Research Matters, Absolutely, working to crystallize de Tocqueville for my own understanding, that we must courageously defend the intellectual freedom that allows truth to flourish, knowing that “Liberty for free thought fused with free will is the foundation of a free society. Nothing else works.”

Academic freedom is fragile. It depends on vigilance, humility and courage. History and Holy Writ teach that no institution can accomplish its mission if it bows to domination, regardless of the direction from which that domination comes. Neglect of this reality does not serve students with ideas, but with ideology.

Walter V. Wendler is the President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns, with hyperlinks, are available at https://walterwendler.com/.