You will find on this site weekly opinion pieces that appear in newspapers in the Texas Panhandle and beyond. I began writing in 2007 and over 600 reflections are posted on this webpage. A few of them are fairly good, I will leave it to you to judge the rest. The early opinion pieces were written while on the architecture faculty at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

The opinion pieces express ideas and views of the power of higher education and its impact on society. These are intended to comment on how universities work and the value they bring to individuals and the larger community – musings intended to cause reflective thought about our nation’s universities… Read More

First in a series on the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. The future of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum is at the forefront of the minds of Texas Panhandle residents and, indeed, anyone who values the history of this remarkable region. This week, I will explain why I believe the WT campus—which represents and serves the Panhandle’s communities […]

President Wendler's Media Appearances

Recent Opinion Pieces

These are the 10 most recent published opinion pieces. Want to see more? Click “View all Opinion Pieces” to browse the full archive, or use the search & filter tools to quickly locate an opinion piece or topic that interests you.

Op-Ed Series Collection

Below, you’ll find a collection of the Op-Ed series, each centered around a unique theme. Select a series to explore related opinion pieces and follow the conversation.

Dr. Walter Wendler

WTAMU President

AUTHOR

About the Author – Walter Wendler

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University and former Chancellor of Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He is also a distinguished alumni of the College of Architecture at Texas A&M University.

He was appointed to the position of President at WT in September 2016. He began his tenure as Chancellor of Southern Illinois University Carbondale on July 1, 2001 and completed his contract in 2007, and returned to teaching Architecture.

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University and former Chancellor of Southern Illinois University Carbondale. He is also a distinguished alumni of the College of Architecture at Texas A&M University.

He was appointed to the position of President at WT in September 2016. He began his tenure as Chancellor of Southern Illinois University Carbondale on July 1, 2001 and completed his contract in 2007, and returned to teaching Architecture…………

Walter V. Wendler’s E-Books

President Walter V. Wendler’s e-books are a vital part of his outreach to current and future students. The books, which collect some of Wendler’s most impactful essays, detail what students should look for in a college, offer insights on community colleges and impart lessons on fiscal responsibility. More essays may be found at walterwendler.com.

List of E-Books

-

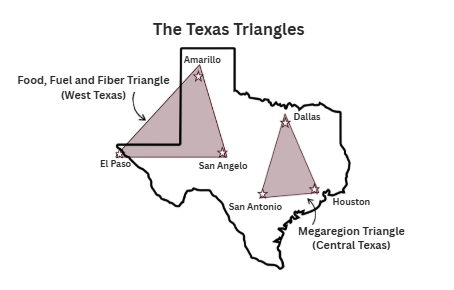

The Texas Triangles

By Walter V. Wendler, President -

Regional Universities Matter

By Walter V. Wendler, President -

The Hill Institute

By Walter V. Wendler, President -

Merit

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President -

Thoughts from a Conservative Outpost

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President -

A Culture of Engagement

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President -

Considering College

By Reflections from West Texas A&M University President Walter V. Wendler with a Foreword by John Sharp, The Texas A&M University System Chancellor -

Community Colleges: West Texas A&M University’s Partners for the Future

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President -

Student Debt

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President -

Intercollegiate Athletics

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President Michael McBroom, Director of Intercollegiate Athletics -

Philanthropy in Higher Education

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President Todd W. Rasberry, Ph.D., Vice President for Philanthropy and External Relations and Executive Director of the WTAMU Foundation -

Student Life

By Walter V. Wendler, WT President Mike Knox, Vice President for Student Enrollment, Engagement and Success

President Wendler Christmas Greetings

2024 The Light of Christmas

2023 Panhandle Values

2022 Celebrating the Sound of West Texas Buffalo Marching Band

2021 On, On Buffaloes

2020 It’s Time for a Change

2019 Season of Change

2018 A Couple, Christmas and Kimbrough

2017 A Special Christmas Story

2016 The Joseph A. Hill Memorial Chapel

Subscribe to Reflections from WT

Sign Up for Dr. Wendler’s Op-eds by E-mail