Leadership in any organization implies and requires transformation. Change in purposeful groups of people, large and small, creates discomfort. Organizational discomfort sometimes matures into a labyrinth of processes that stymie evolution in every corner of the hierarchy. Numerous excuses apologize away the morass of rules and regulations, but chief among them, from a shade tree mechanic shop to General Motors, is the unwillingness of people to accept responsibility for decision-making. Eventually, process becomes a placebo for active decision-making. Process becomes purpose.

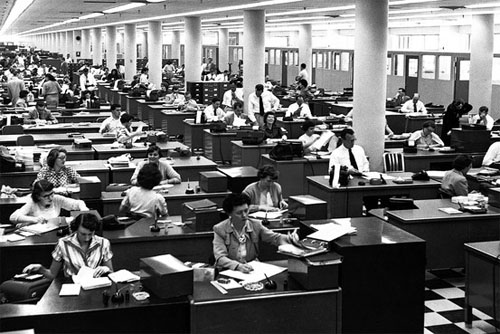

The typical organization has a complex set of rules, regulations and policies — both those formal and organizationally appropriate and those detached from purpose (“Mrs. Jones did it this way for years … it must be right.”) They readily convert administrators and employees into mind-numbed decision-making machines with absolutely no personal accountability or responsibility, real or imagined.

This status quo guarding mentality can overtake an enterprise of just two people, but becomes especially torturous as organizations grow in size and complexity. Process as a substitute for leadership, like all substitutes for leadership, undermines purpose and effectiveness.

In the 1980s a wave of thinking proclaimed that self-management was better than organizational leadership. A self-managed group’s members may individually work towards different or conflicting ends and encourage processes as a replacement for a commonly shared vision. Any sound leadership environment elevates and celebrates the concept of personal responsibility for organizational excellence directed towards shared goals — unlike self-management that says “I’m OK, You’re OK” even though the organization may be suffering terribly. In public education, arguments abound suggesting that self-management is the antidote for the creativity-limiting and controlling influences of leadership. In learning environments there is some legitimacy in the precept of self-management. Teachers in classrooms must have a genuine and independent “shepherd’s heart” in working with students. They know what’s best. On the other hand, some teachers are not bent towards serving students but self, and seek processes that protect them from actions to correct deficiencies or that set direction for positive transformation with which they personally disagree.

The appearance of a rational process may dangerously become more highly valued than substantive decision-making (a strange Machiavellian twist). Intuition and reasoning, while different mechanisms for arriving at decisions and leading, are bedfellows. The perception of rationality and accessibility to a clear way of thinking are important, but in modern bureaucracies has become a dog-eared substitute for substance. In simple terms, the view that a process repeated endlessly produces a rational result is referred to by George Ritzer as “McDonaldization.” Breaking down complex decisions into a dozen rubrics to which weights are applied may yield judicious consistency but, simultaneously, poor decisions. Here is some organizational arithmetic: Second rate decisions arrived at through first rate processes equal third rate results.

Performance reviews of people in any enterprise, from top to bottom, are time consuming. At Deloitte, it was estimated that the 65,000 employees spent 2 million hours evaluating employment performance, while 68% of the executives “believe that their current performance management approach drives neither employee engagement nor high-performance” according to the Harvard Business Review. The thinking goes that an organization that spends this much time on performance evaluation must achieve higher performance. If a little is good, a bunch is better. This substitution of evaluation processes for leadership decision-making does not work. Results untethered from human relationships, assessments, suggestions, and from a work environment that values individual expression and decision-making over procedural regularity lack luster. The legalistic implications of predictable replicability and mindlessness in the application of an adopted protocol don’t necessarily yield effective results.

Process is not a substitute for leadership. Seniority, titles, personal attributes, and management don’t create leadership. Vision, ethical behavior, empowerment and influence are the attributes that make leaders according to a Kevin Kruse reflection in Forbes.

Relationships rather than rules create leaders, healthy organizations, and places where people like to work. And those relationships always require commitment, tolerance of different perspectives, engagement and a deep sense of purpose.

Rational processes support leadership but don’t equal it.