This commentary was published five years ago. Current discussions regarding standardized tests make it worth a second look. It has been tuned up.

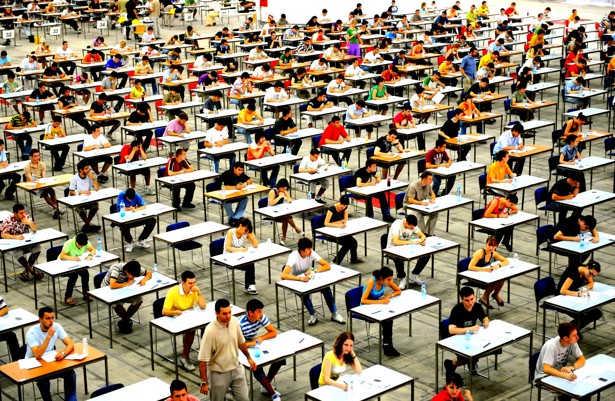

ACT: For many, these three letters spell something that happens in front of an audience or television camera. For millions of high school graduates seeking entrance to a university, they are the bane of their existence in the transition between high school and the rest of life.

The ACT and the SAT are letters without names anymore because the idea of achievement and aptitude in and of themselves are seen as negative by many university leaders. Standardized tests were created as a way to level the playing field in college admissions with data, rather than social status. Early proponents believed equal access to college would provide, through unfettered opportunity, a better world. James Conant, president at Harvard during the thirties, was a strong proponent of this then new view of “merit-based” admissions.

Fast forward to 2015. In the early twenty-first century, many want to level the playing field in college admissions with something other than data. The perceived value of standardized testing is being diminished. Now college presidents claim that the very thing that Conant and others thought was leveling the field actually creates unfair advantage. Increasingly, universities claim they cannot achieve a healthy, diverse student body with socially biased ACT or SAT tests.

People who live in large houses, in affluent suburbs carrying digital devices in every pocket, perform better on the ACT.

If you ranked all ZIP codes in the nation by mean family income and listed the average scores of ACT takers alongside, ZIP by ZIP, nearly perfect correlation would exist. People who come from perceived “privilege” do better on these tests than those who don’t. They also drive better cars, wear genuine leather, and rarely buy knock-off bags and watches on street corners.

These tests all create exclusivity, the same kind that makes a high school halfback who runs a 4.3 second 40-yard dash more valuable on a football field than one who runs a 4.9 second 40-yard dash. Speed is a form of merit, just like the ability to score well on a standardized college entrance test.

In both cases there is the presence of a more or less objective measure.

There are some halfbacks who might be a bit slower and actually be better football players. Likewise there are some ACT takers who might score a little lower but still make excellent students.

The student with the 34 on the ACT and a 4.3 in the 40 makes both admission officers and football coaches salivate. Not one or the other in this kid’s case, but a wholehearted effort to bring them in at any cost, no matter the socio-economic status or zip code.

Admission officers need to look at a combination of indicators to determine fitness for study. The ACT, class rank, high school GPA, courses taken, activities participated in, creating a flexible formula of sorts, will give a pretty good indication of potential success in the university. No university president or admissions office can argue that.

If the current and growing disaffection with standardized tests for their bias leads to throwing away other evaluation tools in college admissions, American higher education is in very deep trouble. Relying exclusively on one indicator is wrong, but throwing all objective measure would be tragic.

A note of hope for students: If you do not perform well on standardized tests, here is a suggestion, one that I took myself. Go to a community college, take demanding courses, save money, and test the waters. If you perform well, you will be prepared, ready for study at a university, or be able to seek a good career that brings you satisfaction based on your abilities. In either case, you will have succeeded.

You. Your work. Bias-free.

Photo Credit: The Atlantic