from www.businessinsider.com

from www.businessinsider.com

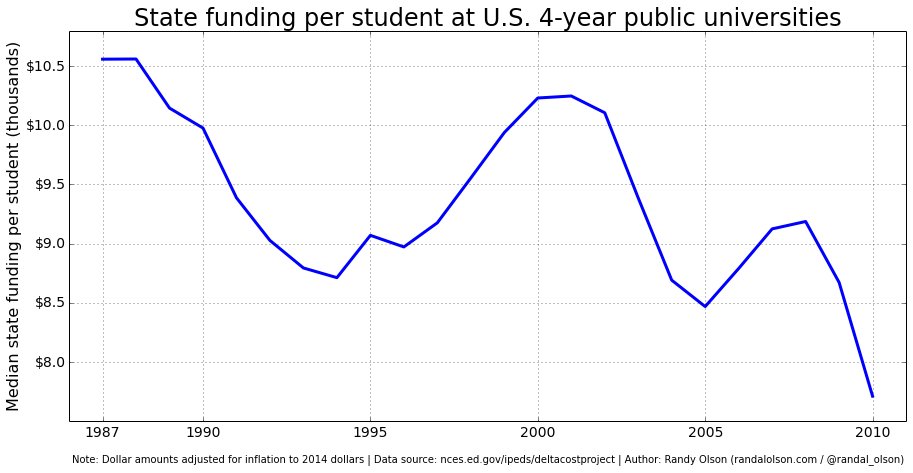

State funding to universities over the past 50 years has decreased. As one example of this state and national trend, West Texas A&M University received 49% of its total budget from the state treasury in 1968. By 2017, the state contribution had been reduced by half, accounting for 24.4% of all expenditures. Tuition and fees in 1968 accounted for 15.2% of total spending. That number has more than doubled to 35% in 2017. Gifts, grants and contracts, (philanthropic income, research income and other contracted sources of revenue) have risen from 7.2% to almost 19%. Auxiliary income (room and board) has decreased from 24% in 1968 to a little over 10% in 2017. Sales, services and interest have increased from 4.4% to 11.4% in the same period. Resource flows are changing. When state contributions decrease, other resource flows must increase, or services and offerings are changed.

A recent study from The Center of Budget and Policy Priorities marks national higher education funding trends from 2008 to 2016. Four states saw increases in state funding over that eight-year period: only Montana, North Dakota, Wisconsin and Wyoming spent more on each college student than in 2008. Typical decreases in state support hover around 20% to 30% over the last decade. Arizona and Illinois have seen dramatic 50% reductions. Reductions in Texas over the past decade have been a nationally modest 17.2% and are improving incrementally.

Trends are universally clear and neglecting these changing patterns is a liability leading to ineffectiveness.

The need for increased tax dollars to support federal aid and a more robust state support of higher education is real. In addition, primary and secondary education needs, healthcare costs, public safety, infrastructure and other demands on government coffers are persistent, universal and immediate.

Recent proposals to tax tuition waivers and graduate student stipends create unintended consequences, according to University of North Carolina System Chieftain and former Secretary of Education under President George Bush, Margaret Spellings. Opportunity for all comes from reducing tax burdens, not increasing them. Taxing stipends and scholarships could lead to taxation of other charitable giving to universities and evaporate a critical resource stream in higher education. The idea of taxing university attendance is chillingly antithetical to a strong republic. Even more troubling – churches and temples, the American Heart Association, the United Way, the UNCF and hundreds of sundry enterprises intended to stimulate positive personal, social and community well-being may be next.

Universities tend to present an unsympathetic public face. For decades, as student debt has risen with underemployment and unemployment of college graduates increasing and the fiscal viability of college degrees appearing to decrease, colleges seemed indifferent. My experience in numerous university settings does not support that perspective. However, too often, perception equals reality.

The single greatest impact on resource flows is reducing absolute costs to students, families and universities. Rigorous engaged assessment of every resource and its use – state appropriations, tuition and fees, gifts and grants, auxiliary income, sales and services and family savings – is required. Flexibility and innovation might be attractive to an increasingly wary population of students. The need for access to higher education is real. Over the next decade, 65% of the workforce will require some form of market responsive, postsecondary educational experience. Study for the sake of study, disconnected from economic reality, will not work. Nearly 70% of the student population must borrow to attain a college education.

A degree with high debt and low employment utility is a wolf in sheepskin’s clothing. (For younger readers, “sheepskin” is an old colloquial expression for a diploma.)

Responsive universities should help lead the way out of this quagmire. Students and families should be well informed of the costs and benefits of a particular degree from a particular university before enrolling. Generalizations fail. A commitment to clearly communicating degree costs and potential starting salaries, in response to realistic debt loads, is required. A recent bipartisan proposal from U.S. Senators Rubio, Warner and Wyden–the “Student Right to Know before You Go Act”—has value, but it will surely be imperfect. If a student changes majors or stops or opts out to get married and/or tend to a family situation, resource requirements, time to degree and starting salaries all may change.

Students should be encouraged to investigate alternatives to the traditional four-year university experience. Resource implications follow if community college or dual-credit opportunities through high schools are exercised. Viewing the experience in concert with work and family life, even if it takes eight years to complete a degree, might work best for some. A professional internship might be a degree requirement. Work experience heightens the possibility for discipline related employment upon graduation, and resource flows change. There are no panaceas here. Every strategy requires careful analysis of short- and long-term costs and benefits. Students are not customers, but the timeless rejoinder of caveat emptor, or buyer beware, applies. Every one of these suggestions require a reconfiguration and an individualized partnership between student and institution.

One size fits only one, not everyone.

My father and my father-in-law advised me to “get any college degree because it is worth it.” That advice was rock-solid in 1968. However, a half-century later, that counsel may not hold water. This reality is the truth of contemporary cost and value equations in higher education.