Eighth in a series on what to look for in college.

Borden County School District in Gail, Texas, on the edge of the Caprock Escarpment, is cut in two by the Colorado River. Borden County is the fourth-least populous county in Texas. Its 648 people are spread over 906.1 square miles creating a population density of 1.398 people per square mile. It’s sparse. If you don’t believe me, get in the car and go. You’ll find ground so beautiful it will take your breath away. And the people? About the same.

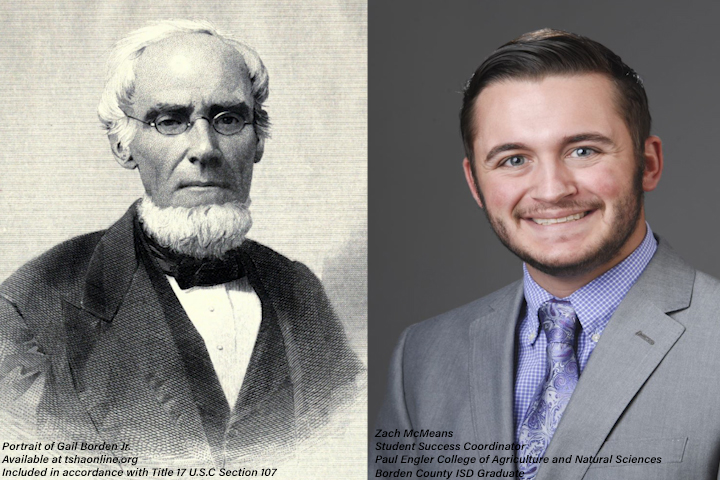

The county is named after Gail Borden, Jr. Mr. Borden accumulated 1.5 years of formal schooling in New London, Indiana, traveled a torturous trail twisting over half the nation from New York to Texas and survived repeated business failures – and a bushel basket full of hard knocks. Through it all, he demonstrated tenacity and reverence for life that thrives in Borden County, crystallized in its capital and solitary city, Gail. It is his legacy.

Borden lost some of his family to yellow fever in the 1840s, creating a lifelong interest in hygiene. Experience prodded him to find ways to more safely store milk. He patented condensed milk. The Borden Company (Elsie the cow) was named to honor him in 1899. His accomplishments include creating a number of other important food inventions, the establishment of churches, helping found Baylor University, Galveston, and, indeed, Texas.

Zach McMeans, a recent graduate of West Texas A&M University, is now a colleague in the Paul Engler College of Agriculture and Natural Sciences while working on a master’s degree. Borden County DNA is in his bloodline, along with a solid education from Borden County ISD. Its excellent people and facilities provide an auditorium that could seat nearly the whole county. His grandfather Mickey McMeans was the principal of Borden County High School for 44 years. His father, Bart McMeans held the same position for 16 years. Zach is a fourth-generation college graduate—rare at a public university. Zach is possibly the only fourth-generation college student currently enrolled at WT.

WT unapologetically values the legacy of place. Geographic legacy affects communities, families, and individuals, creating lively woven lattices of legacy.

The New York Times opined on September 7, 2019, that legacy in college admissions should end. Many institutions give admission credit, some would call it preferential treatment, to “legacies,” those students who are the offspring or relatives of previous graduates—a “who you know” benefit. The Times claims that 75% of the students at Ivy League schools have legacy relationships; however, studies often show only modest advantage for legacy admits. One of 1,200 commenters on the New York Times op-ed was a Dartmouth legacy, that was not admitted to Dartmouth. She had to settle for MIT, a “legacy-free” institution.

Valuable programs on university campuses proudly support first-generation college-goers. Being one myself, I carried little from my family life that prepared me for college other than the idea that hard work, tenacity, and grit are all invaluable in personal achievement. I think Gail Borden understood that, but I’m not sure the editorial board of the New York Times gets it.

Students from prosperous and populous places have access to more college-prep courses, higher-level offerings in mathematics and science, and other seeming advantages provided by circumstances of geography. There are different benefits of geography in places like Gail. The McMeans family is evidence of that. Not only have four generations of that family made meaningful contributions to the local and extended communities, but they are leaving a living legacy of place.

On our way into Gail, Zach saw a man in a nondescript pickup. He pointed to the truck and the gentleman driving it, saying, “That’s the County Sheriff.” Zach hasn’t lived in Gail for six years, but he still knows the people of the community and they know him. When we entered the Coyote Country Store and Café, Zach was greeted by the owner, a former school teacher.

She said but one word as we entered this remarkable place to eat: “Zacho!”

If you visit a college campus and the people on the campus don’t appear to appreciate the place, have a commitment to it, know something of its history and its citizens, and demonstrate pride in being there, leave immediately. It will not be a good place to study. They don’t understand geographic legacy.

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns are available at http://walterwendler.com/