Walter Wendler, West Texas A&M University President and John Sharp, The Texas A&M University System Chancellor

Sixth in a series on Regional Universities

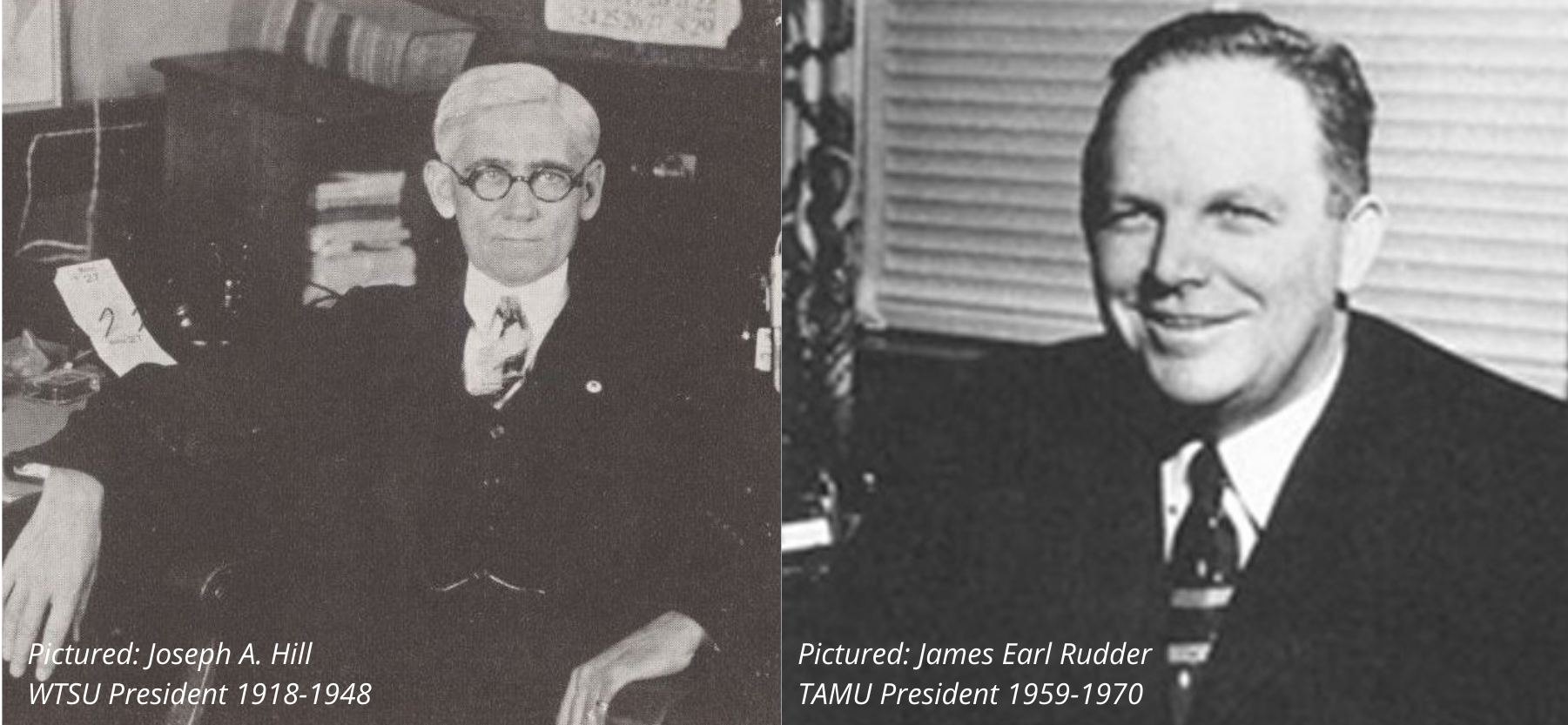

Some university leaders have had a transformative impact on their institutions and, in turn, the larger community. Leadership excellence is leadership excellence, no matter how, where or when it occurs. Earl Rudder at Texas A&M University lead transformative change that helped turn an undergraduate military school into a leading world university; the seeds of his effort continue to germinate. He was fearless and committed to forward-looking change, and it happened. Clark Kerr at the University of California envisioned a state-wide organization that provided an unparalleled opportunity to thousands of Californians in three different kinds of higher education settings, and it happened. Theodore M. Hesburgh at Notre Dame recognized that a university could, and indeed should, impact the world through the application of deep principles of his faith in the public square that recognized the power of the University as a beacon for the larger social order, and it happened. Leadership does not stop there, however. Joseph A. Hill at West Texas A&M University held deep principles that informed every university decision made in response to the power of the Panhandle, and it happened.

President Hill led West Texas State University beginning in 1918 and concluded his tenure in 1948. The greatest depression in modern history, the greatest war the world had ever experienced, and the birth pains of a social revolution in the life of the American Experiment did not deter him. Hill repeatedly stressed the importance and power of individual responsibility that coupled the exercise of responsibility to results. Many contemporary forces seek to transfer responsibility from individual to state. Hill and other university leaders “worth their salt” exercised transparent guidance through principle-driven leadership.

Texas A&M University President Earl Rudder was singularly committed to purpose and rugged individualism in everything he did. According to Thomas Hatfield, “He was simply an authentic person who had a calling in his life. He was very purposeful, with values that were as firm as was his character. He was one of the greatest citizen soldiers.”

Hill didn’t believe in social guarantees but a level ground that provided an opportunity to all. Other than fairness, guarantees can become thieves of the human spirit, grievously robbing men and women of aspiration. Nothing undermines a free society more than actions that diminish personal aspiration. Hard work and determination were the cornerstones of Hill’s perspective that recognized this reality: Not everybody gets a blue ribbon. Emotional toughness is essential.

Hill identified the importance of free moral agency and free thought as part of the university experience. In a speech entitled “Educational Implications of The American Theory of Government,” before the annual conference of County Superintendents and County Supervisors at The A&M College of Texas, July 29, 1935, he made this prescient observation: “A fact of first importance in the democratic theory is the capacity, the right, and the responsibility of the individual.” He went on to state, “The Declaration of Independence proclaims, among other things, that every human being has measureless capacity for the abundant life; that he has an inalienable right to the opportunity to attain it; and that he is under heavy obligation to the society that makes this attainment possible. Not one of these three elements of the American system can be omitted without serious danger to our whole governmental and social structure.”

In Thomas Jefferson’s “Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom,” there is a clarion call for free moral agency that resonates with Hill’s rugged individualism and Rudder’s “values that were as firm as his character.” Jefferson wrote, “Whereas Almighty God hath created the mind free . . ., that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments, or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness. . .” This perspective helps create vitality and value in the University experience.

Eighty years ago, voices cautioned all regarding a shift from individual responsibility and accountability towards holding the state accountable for individual outcomes. There was legitimate fear that Jefferson’s free moral agency, Hill’s rugged individualism, and Rudder’s emotional toughness would imperceptibly disappear. Personal responsibility could not, and cannot, be bartered away for material prosperity or social guarantees. Such thought rots the core of the American dream and the value of a university experience.

Rudder and Hill recognized human nature’s darkness and light. Self-interest in isolation, or personal progress attained by toil and treasure in varying degrees, is neither good nor bad. Rather, as noted by Adam Smith in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, while people serve their interests first, they also seek to serve a greater social good. Smith declared, “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it . . ., The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.”

Hill and Rudder combined the very best of these traits from different perches that helped, and continue to help, shape higher education in Texas in ways that have lasting impacts. Presidents Kerr and Hesburgh had nothing on either. These traditions will continue to guide West Texas A&M University and The Texas A&M University System, married in their pursuits of excellence in service to our state.

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University. His reflections are available at http://walterwendler.com/.

John Sharp is the Chancellor of The Texas A&M University System. Read more at https://chancellor.tamus.edu/.