Originally published December 11, 2011, in the Chicago Tribune—slight modifications have been made. As we start the school year, amid a storm of moral relativism, fear and doubt, this may be as appropriate for the autumn and the start of a new year on campus as it was for Christmas, my original intent.

I stood beside a swimming pool in College Station, Texas, two or three times a week for two years, watching my sons flailing at the water, trying to shrink their time in a 25-yard spurt of breaststroke, backstroke, butterfly and free medley.

Next to me, week after week, stood a fellow who became my friend—Mike, an affable guy, ruddy complexion, committed to doing things well, a good scholar and a stunning example of an Irish Catholic. He watched his daughter while I watched my sons. As you might imagine, the nuances of the various swim strokes were quickly vacated for a more engaging chitchat.

Over time, we became friendly, and discussions we had over the din of the children learning and playing turned to topics friends can engage in that acquaintances can’t. Mike was penetrating in his analysis of the human condition.

He also cussed like a sailor and relentlessly and unreservedly voiced his disdain for the Catholic Church. Yet every week, he took his daughter from the swimming pool to catechism class. Never missed a beat.

One day I asked him about the apparent inconsistency between his complaints and his actions. He said without hesitation or apology that his daughter needed something to rebel against, and the Catholic Church was a perfect foil.

I started to object, but he was steadfast. He felt that even though he disagreed with the church’s stance on any number of topics, everyone needed some fixed point from which to navigate—a personal North Star.

I’m not sure he fully believed what he told me; I never could get that out of him despite my best efforts. I know he was sincere about instilling a moral standard, something seemingly sacrificed on an altar of scientific and social sophism, even an inflexible standard that might appear to have imperfections, distortions, defects, tears and stains.

Aside from the fact that my frame of reference was exactly the opposite of his, I agreed with his logic. Informed by my relationship with God, I have found in Christ an example that is perfect, clear, whole, consistent and faultless. I guess you could say I have a different personal star, the one that rose over Bethlehem—not College Station or Dublin, in the eyes of my good friend.

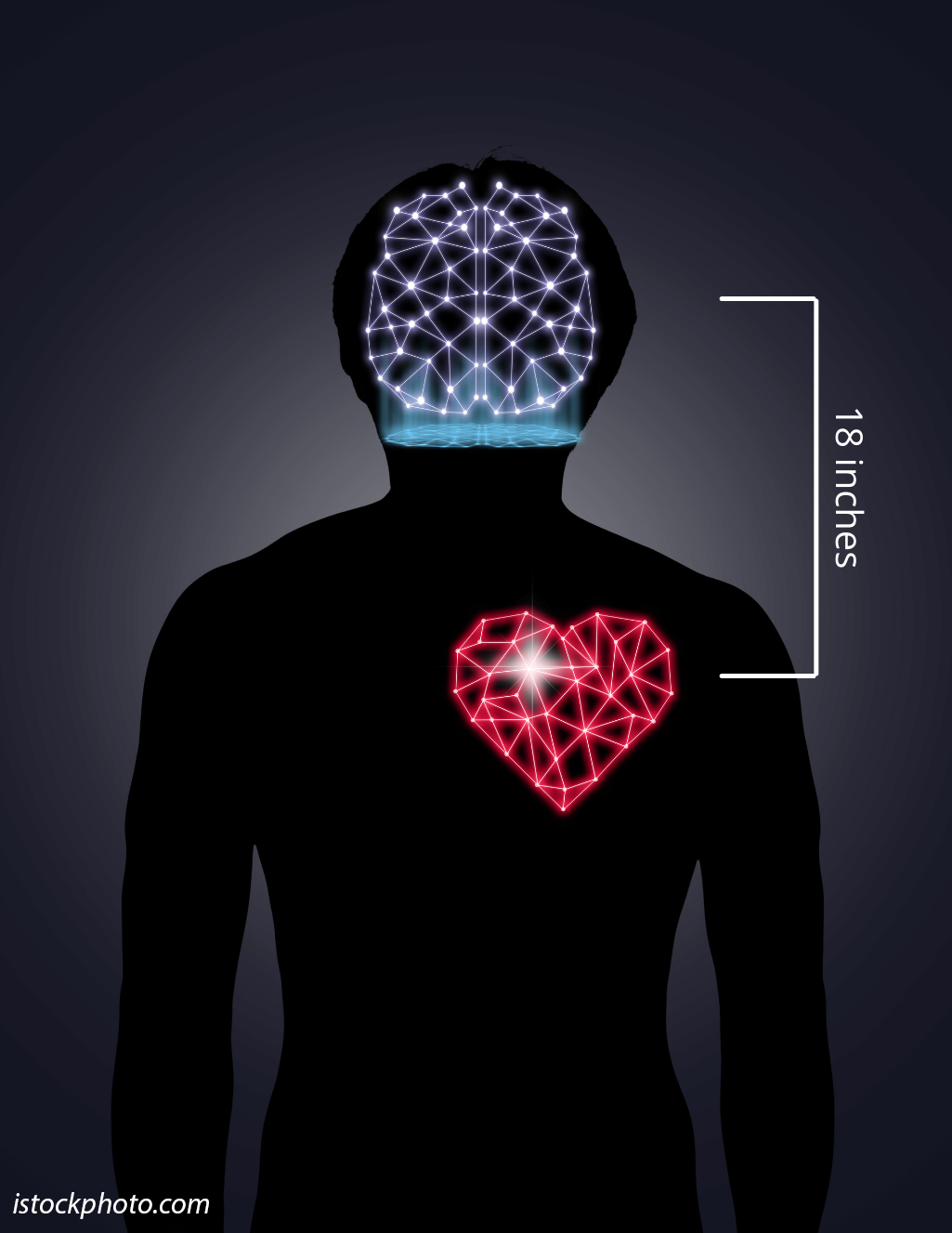

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to start a tradition that included bringing faculty, staff and friends of a university together to wish each other well during the holiday season. After an hour of visiting, a pianist accompanied hundreds of us, physicists and plumbers, teachers and trainers, groundskeepers and geologists, secretaries and scholars as we sang (I may be generous calling it that) Christmas songs. To this day, I think of that noise we made and hear music in my heart—you know—the one that is 18-inches from my head.

It was joyful.

It didn’t mean the same thing to everyone, but I think it meant something to everybody, even if only that we belong to something bigger than just ourselves.

The tree, gifts, families, friends and the other secular trappings touched common memories, and we all knew that we weren’t alone in the dark, cold night. We did not have to share a single meaning to find meaning in the shared experience.

But we could sing, drink coffee, eat cookies and acknowledge each other.

It seems the job of postmodernism is to separate head and heart. This 18-inch distance is wreaking havoc on our social order. Contrary to what some physicists and biologists think, science and ethics can coexist quite nicely. There should be room for this discussion.

Science is not “truth.” Science is a method for finding a particular kind of truth. Other methods let you find truths, and science cannot; truths can lead us to become who we need to be and help us build stronger communities.

When we only accept the icy standards of measurable phenomena, 18-inches becomes an impossible distance.

Thanks for your indulgences. It must be that time of year. I’m convinced that that day reduced the distance between the hearts and heads of hundreds of dedicated servants from 18-inches to zero, if only for an instant. In a sense, like the start of a new school year, even in the midst of public hand-wringing, trepidation and what seems to be abject fear.

Walter V. Wendler is President of West Texas A&M University. His weekly columns are available at https://walterwendler.com/.